Overview

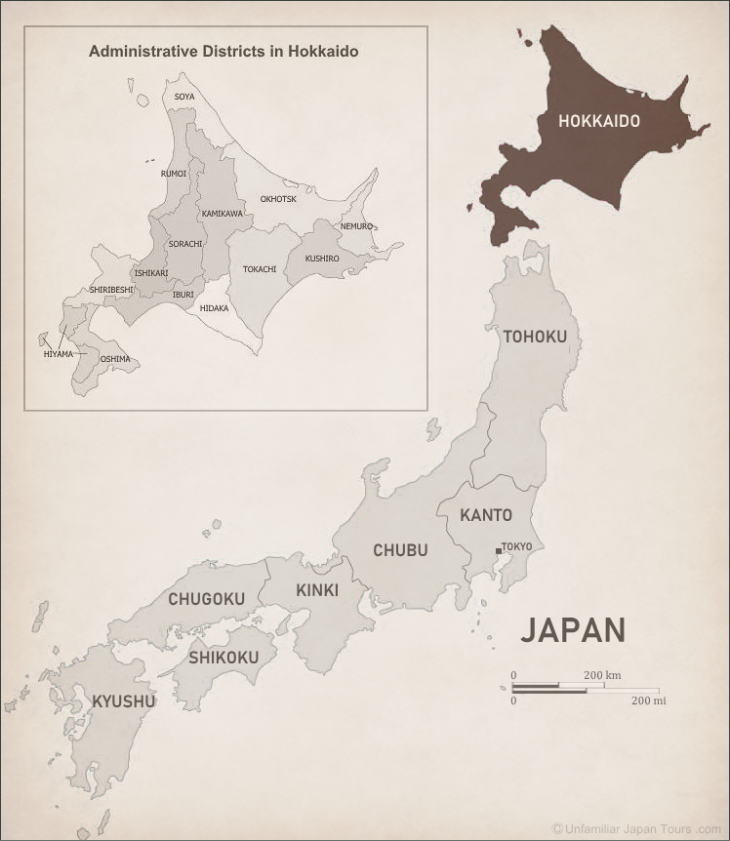

Hokkaido is the northernmost Region of Japan. The main island of Hokkaido is the second largest, next to Honshu, of Japan’s four largest islands. It faces the northern tip of Honshu across the Tsugaru Straits, and the southern tip of Russia’s Sakhalin Island across the Soya Straits. Unlike the other three main islands of Japan, Hokkaido does not consist of several prefectures. But the entire Hokkaido Region makes one big prefecture (although we usually don’t call it ‘Hokkaido Prefecture’ but simply ‘Hokkaido’).

The land area of Hokkaido accounts for about one-fourth of Japan’s entire land mass. However, with most of its population concentrated in big cities like Sapporo, the population density of Hokkaido is extremely low. And a large portion of this vast land is used for agriculture or as pasture for dairy cows.

Agriculture in Hokkaido is often characterized by its large-scale operation using machinery. This style of agriculture is not necessarily typical in any other part of Japan. So, many Japanese today might associate Hokkaido with this dynamic landscape of green fields or meadows that seem to go on forever.

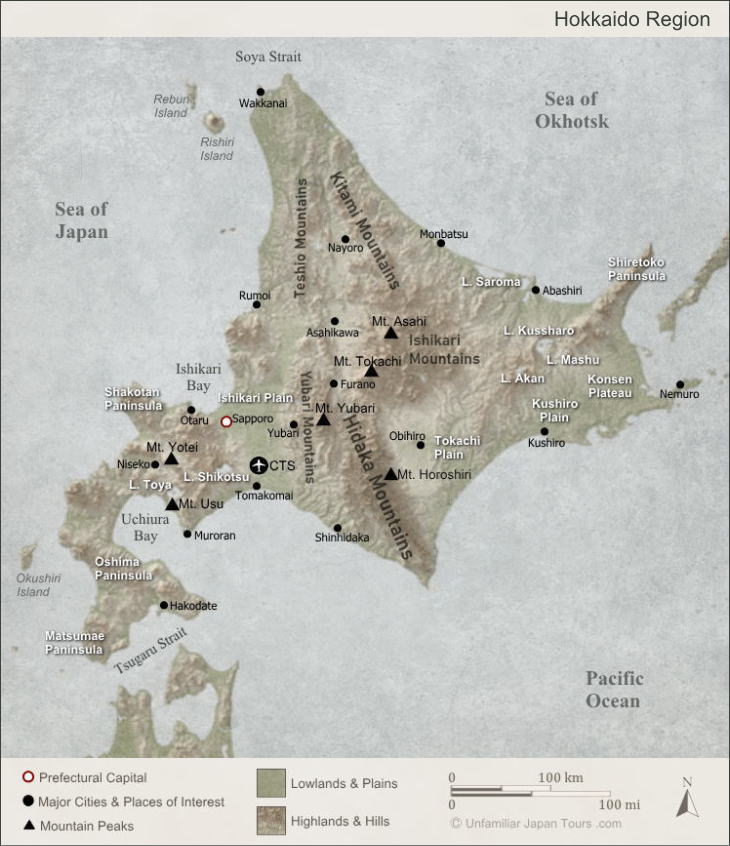

Map of Hokkaido

Shiretoko

On the other hand, Hokkaido still has a considerable amount of pristine environment that has not been greatly spoiled by human beings. Among these natural places, Shiretoko in eastern Hokkaido is worth a special mention.

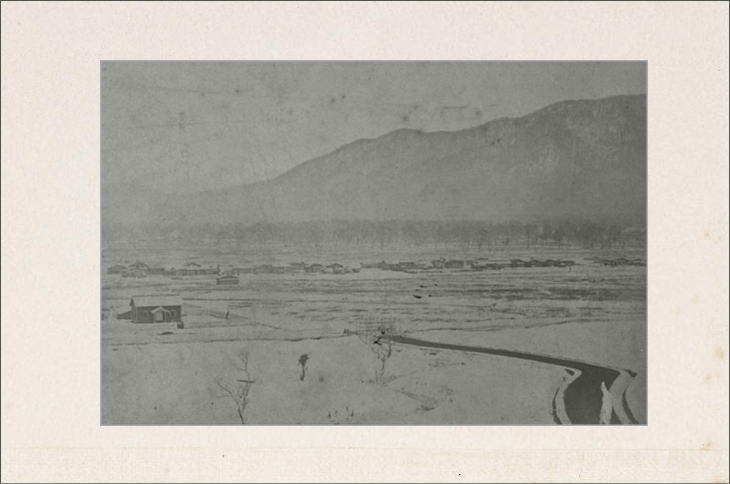

The Shiretoko Peninsula extends a long distance into the Sea of Okhotsk. The winter climate of this area is especially harsh, with a lot of snowfall and the cold seasonal wind blowing from the west. At the center of the peninsula runs a series of volcanoes. They include sulfur-spewing Mount Iou, and the Shiretoko’s highest Mount Rausu at 1,660 metres. Precipitous cliffs dominate most of the peninsula’s coastline. And some of them reach as high as 100 metres. Largely due to these severe environmental conditions, Shiretoko has long avoided large-scale human exploitation.

Drift Ice in Shiretoko

In the period roughly spanning from late-January to mid-March, drift ice fills the sea off the coast of the Shiretoko Peninsula. Shiretoko is the southernmost place on earth where one can observe drift ice in the Northern Hemisphere.

These ice floes contain, and also bring about, rich nutrients and micro-organisms, which attract fish like salmon and trout. And these fish, in return, become the feed for many birds and mammals, such as Hokkaido brown bears, white-tailed eagles, Blakiston’s fish owls, and killer whales. With this dynamic food chain, as well as the existence of a wide variety of living creatures, a large portion of the Shiretoko Peninsula and its surrounding sea zone became UNESCO’s natural World Heritage Site in 2005.

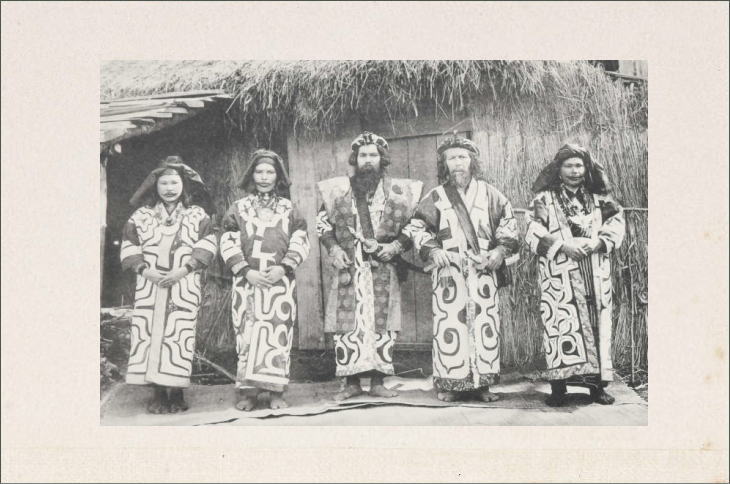

The Ainu

Hokkaido’s indigenous people are the Ainu. Hunter-gatherers, they lived in straw-thatched houses called cise (pronounced “chee-se”). Cise were built in hamlets called kotan. The Ainu chose locations of kotan carefully by considering the likelihood of natural disasters and food acquisition. Living in harmony with the land, they believed that kamuy (god) dwelled in all natural objects.

So, they often named places after the natural environment. And some of these names are familiar to us Japanese today. For example, the name of Niseko, which is in western Hokkaido and has become very popular internationally as a ski resort town, originated from an Ainu word. It means ‘the river gently meandering through a steep cliff’.

In fact, until 1869 when the name Hokkaido was officially introduced, Japanese people called the island Ezochi. That means ‘the land where the Ainu live’. On the other hand, the Ainu themselves called the land Ainu Mosir, meaning ‘the earth where the people live peacefully’.

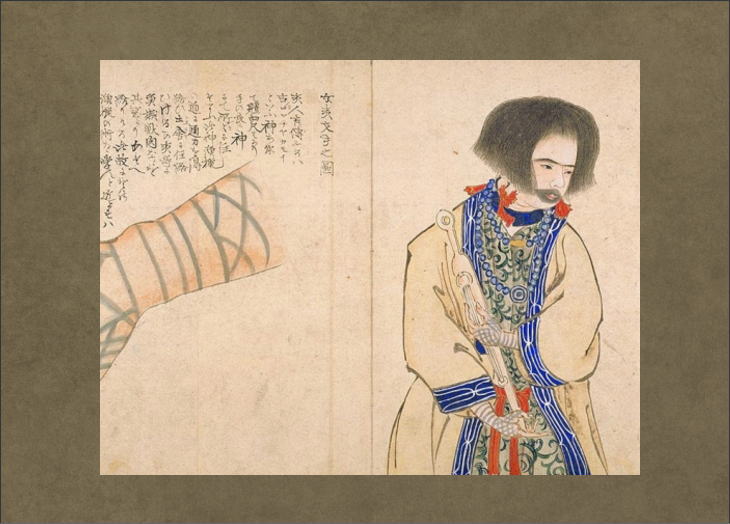

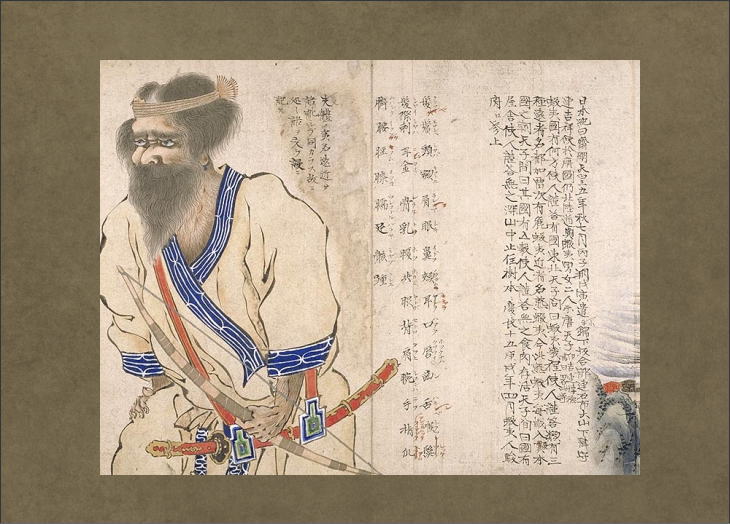

Conflict with Wajin

They say it was in the Kamakura Period (1192-1333) that the first wajin, Japanese from the main island of Honshu, came to settle in Ezochi and started trading with the Ainu. Under the Tokugawa shogunate in the Edo Period (1603-1867), the Matsumae-han (Matsumae Domain), based in the southwest part of Ezochi, monopolized exclusive trading rights with the Ainu. However, partly because of the partial trade conditions imposed on them, Ainu people became increasingly frustrated with the Matsumae clan and the mainland Japanese.

In June 1669, the biggest rebellion in Ainu-Japanese history took place. People call it Shakushain’s War (or Shakushain’s Revolt) after the name of the Ainu leader of this rebellion. Reportedly, in a series of battles, some 350 wajin were killed by Ainu rebels throughout Hokkaido. But Matsumae, pleading with the Edo shogunate, managed to get additional soldiers and ammunitions from the main land. In the battle of Kunnui, Matsumae soldiers used two hundred matchlock guns to contain the southward advance of the Ainu. But the Ainu soldiers, on the other hand, chose to fight with their conventional weapons, which were poison arrows (even though they had several matchlock guns).

Then, gradually the tide of the war started to turn against the Ainu. Shakushain and other Ainu generals were killed in October and their primary headquarters, Shibuchari Casi, finally fell in November. After the battles, the Matsumae-han started to keep Ainu tribes throughout Ezochi on a tighter leash.

Development of Hokkaido

By the late-19th century, there were still a lot of wilderness in Ezochi. So, in 1869, the new Meiji government, which had just replaced the Edo shogunate two years before, established an government office called Kaitakushi (or Development Commision). And they embarked on a large-scale development project. Coinciding with this, the new name Hokkaido was granted to this northern land.

Under the auspices of Kaitakushi, a lot of people moved to Hokkaido and engaged in developing the land and infrastructure. Many farmers came from the main island of Honshu. Some of them had been forced to abandon their native land due to natural disasters or other misfortunes. And they were looking at this frontier land as a beacon of hope.

Farmers often formed large parties for the purpose of immigrating. And once they established a village, they sometimes named the newly developed land after their native town. For example, present-day Kitahiroshima City (kita means north in Japanese), which is about 20 km (12.5 mi.) southeast of Sapporo, was originally explored and established by farmers who hailed from Hiroshima Prefecture in western Japan.

Tondenhei

Also, among immigrants were members of the former bushi class (samurai warriors). They had been deprived of some privileges, including the right to carry swords, as a result of the fall of the Edo samurai government. So, they were looking for the jobs and new opportunities, and the government hired many of them as tondenhei (屯田兵).

Tondenhei were soldier-farmers. And they tackled the development work and also prepared for a possible threat from Russia to the north. They usually worked as farmers. But every time a war broke out, they were called upon to be soldiers. (While early tondenhei consisted mostly of former samurai, subsequently the government started to hire a lot of commoners.)

Father of Hokkaido Development

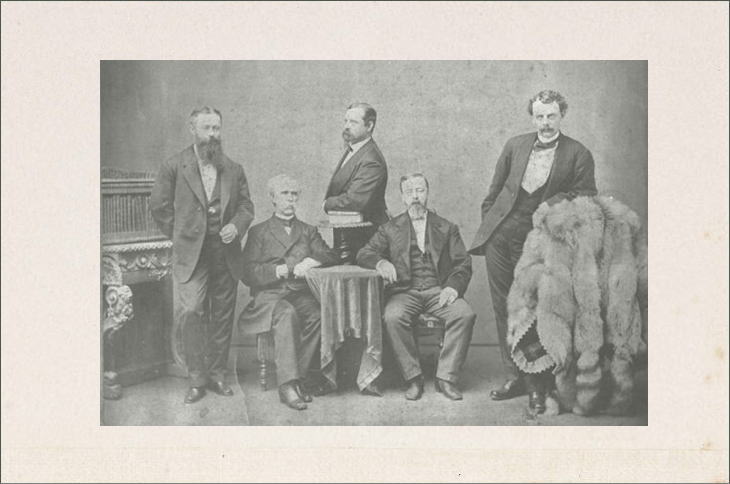

It was in the 1870s that the Meiji government invited to Hokkaido several distinguished people, mainly from the United States, to learn from their advanced technology and culture. Among them, Horace Capron and William S. Clark are especially well-known in Japan today.

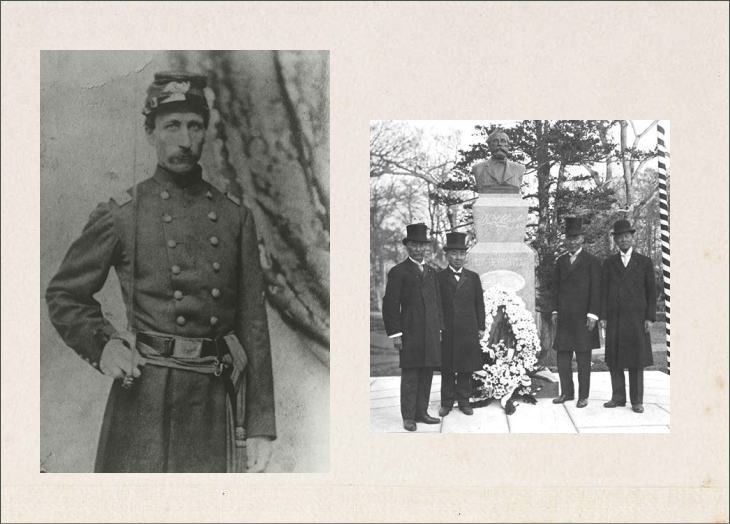

After fighting in the American Civil War as a Union officer, Capron became a commissioner in the Department of Agriculture under the Grant administration. And it was when the Japanese government asked him to take a position as a special foreign adviser for Hokkaido development. During his four-year stay in Japan (1871 – 1875), he made various noteworthy proposals concerning road construction, industry, agriculture, and fishery.

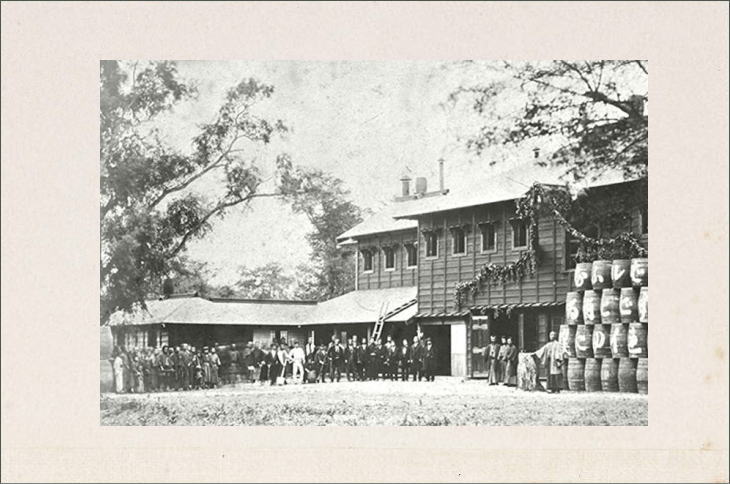

Capron introduced an ‘American-style agriculture’ to Hokkaido. He encouraged the use of farm horses (instead of conventional oxen) and farm machines. He also taught cultivation methods for various farm products, such as corns, hops, and new varieties of strawberries and apples, which were not familiar in Japan at that time. Likewise, Capron encouraged wheat cultivation instead of rice cultivation, saying that the land of Hokkaido is not so suitable for growing rice due to its cold weather. So they say Capron actually laid the foundations for present-day Hokkaido as a ‘Beer Kingdom’. Since his contributions to Hokkaido were so great, people sometimes call him the ‘father of Hokkaido development’.

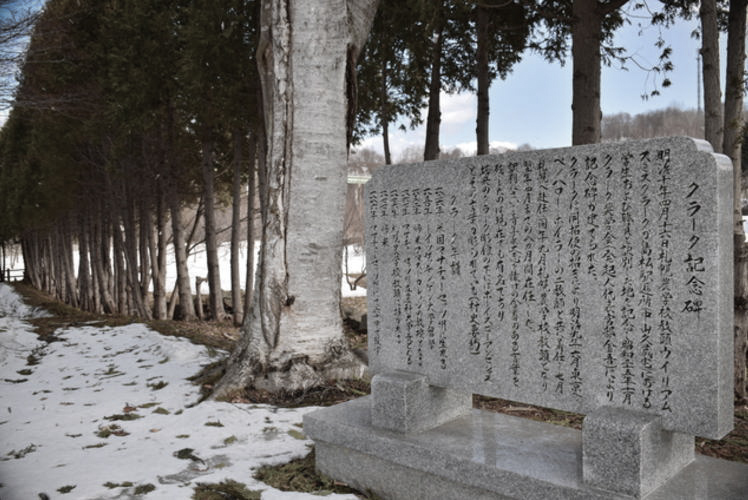

Clark’s Parting Words

Even more well-known than Capron in Japan is William S. Clark. He taught botany and other natural science subjects to the first students of the newly-established Sapporo Agricultural College (present-day Hokkaido University). Many of his students later grew up to be leading figures in the agricultural and economic fields in Japan.

He also distributed copies of the Bible to students to introduce them to Christianity. However, probably most Japanese today associate the name of Clark not so much with his accomplishments in Hokkaido but with his parting words: “Boys, be ambitious!” which is a phrase everyone in Japan knows.

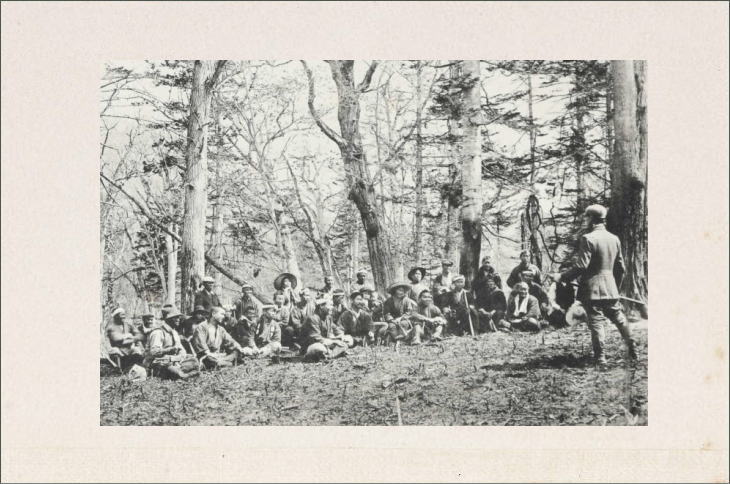

The story goes that on April 16 in 1877, his last day in Hokkaido, his students and the faculty held a sort of informal outdoor send-off for Clark, where he made some farewell remarks and shook hands with each student. Then, according to one of the attendees, “he jumped on his horse and shouted ‘Boys, be ambitious!’ and whipping the horse on its side, started dashing down the snow-slush road until he vanished far into the grove.”

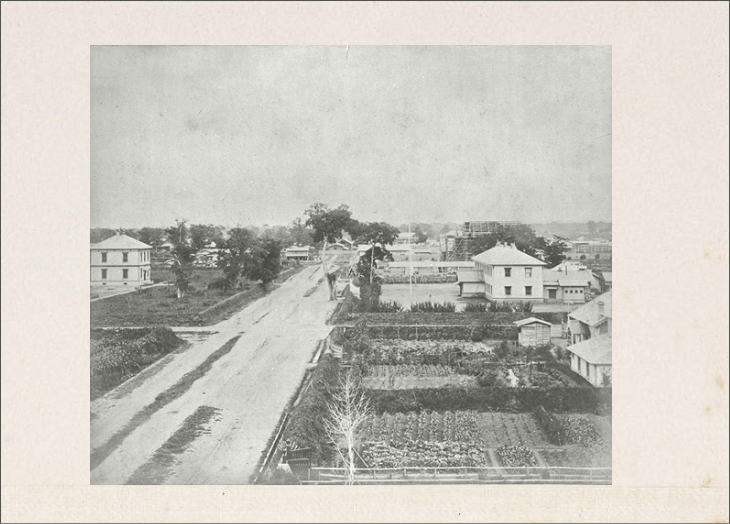

Development of Sapporo

Thanks to these combined efforts from the people inside and outside the country, Hokkaido developed rapidly. The population of Hokkaido, which was a mere 100,000 around the 1870s, reached well over two million in the 1920s. And the capital city of Sapporo, whose foundation owed a lot to the suggestions from Horace Capron, started on the road to becoming one of the biggest metropolises of Japan.

After the abolishment of Kaitakushi in 1882, the Meiji government established the Hokkaido-cho (literally, the Hokkaido Agency) in Sapporo in 1886 to assume overall administrative responsibilities over Hokkaido. And they began to construct its main office building, which was completed in 1888. That very same building is now called the Former Hokkaido Government Office Building (the ‘red brick building’). It is a symbol of Hokkaido as well as a popular tourist landmark. The building now includes a tourist information center and several rooms where we can learn the history of Hokkaido’s development through a number of valuable exhibitions.

Photographs: Properties of Unfamiliar Japan Tours.com, unless otherwise noted.

Outbound Links (New Window)