“Eastern Kyoto” in the above title refers to the area commonly called Higashiyama (literally, “the east mountains”) in Kyoto Prefecture in the Kinki Region. This area includes at least two of the most popular and historically important sights in Japan: Ginkaku-ji Temple (the Silver Pavilion) in the north and Kiyomizu-dera Temple in the south. Both have many buildings and artifacts designated as national Important Cultural Properties (some of them are National Treasures, a higher designation) and both were together added to the UNESCO World Heritage list in 1994 under the name of Historic Monuments of Ancient Kyoto. Besides these two, Eastern Kyoto has Nanzen-ji Temple, the headquarters of the Nanzen-ji branch of the Renzai zen sect in Japan, and Eikan-do (Zenrin-ji Temple), which is one of the best spots in Kyoto for viewing autumn leaves, among others.

I can assure you that visiting these famous places is a wonderful experience. But the trade-off is that you could be just one of a huge number of sightseers visiting that day. So, if you still have some extra time after seeing some of these popular sights, I hope you will also visit a couple of the “hidden gem” type of spots there. They might be less well-known and less crowded than the places I mentioned above, but they could offer you some unique and interesting experiences.

Honen-in (and Anraku-ji Temple)

Honen-in is about a ten-minute walk south from Ginkaku-ji. This Buddhist temple is said to have originated from a humble thatched hut where Honen (1133-1212), the founder of the Japanese Jodo (Pure Land) sect of Buddhism, practiced nembutsu with his disciples. Nembutsu is the reciting of the name of Amida (Amitabha) in order to be reborn in the Buddhist paradise in the afterlife.

It was a 17th-century abbot of Chion-in Temple who actually made the foundation of present-day Honen-in by building some main structures there. Today visitors can freely enter the precinct from 6:00 a.m. to 4:00 p.m. With its green moss, beautiful maple trees and a pond, there is an air of spirituality here.

Temple’s Treasures

In the first week of April as well as in the first week of November, the main buildings and garden are open to the public. The Hondo (Main Hall) contains the sitting image of Amida Buddha, which is the principal image of the temple. And on the shumidan stand in front of the image are placed every morning 25 freshly-picked flowers by a monk. These flowers represent the 25 bodhisattvas who are serving Amida Buddha as attendants. The types of flowers picked differ from season to season. From mid- to late-March, for example, they mainly pick camelia flowers within the precincts.

The Hojo (abbot quarters) is also open to the public in the same period in April and November. The building also has a couple of valuable artifacts, including the set of paintings on the fusuma sliding doors by a 16th century artist, Kano Mitsunobu, which is a nationally registered Important Cultural Property.

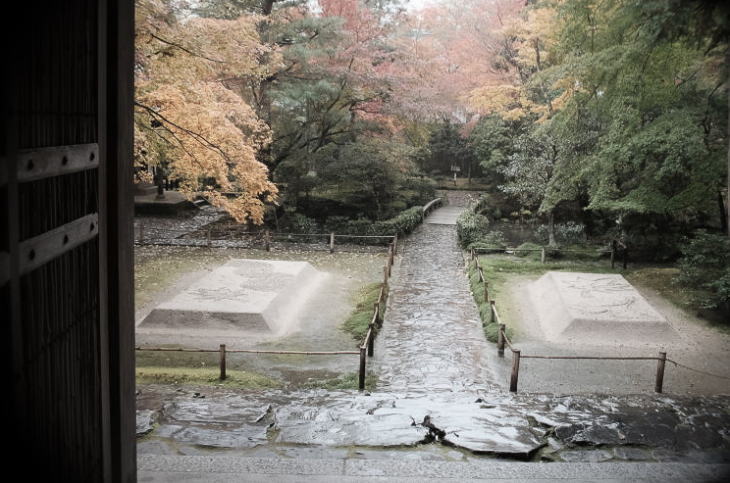

White Sand Mounds

Entering the precinct through the elegant gate with its thatched roof, the first thing one notices would be the unusual mounds of white sand flanking the path. They are called byakusadan (白砂壇) and on them are drawn some patterns. In mid-November 2021, it was a maple leaf that was drawn on the top of one of the mounds. And on the top of the other was drawn a geometric design.

When I talked with the chief-abbot’s wife, I asked her what these mounds with their different patterns represent. She replied to me: “It is not the case that one mound represents one thing and the other represents something different. The two mounds together signify one thing: purification. I suppose the pair of mounds have the same function as the purification water trough placed at the entrance of Shinto shrines. Visitors are purified in their body and mind as they pass between these two mounds.”

“Can this style of mound layout be seen in some other temples in Japan?”, I asked.

“As far as I remember, this type of mound arrangement can be seen nowhere except here,” she answered.

I asked her if these mounds are tended daily.

“Not daily, but periodically,” she said.

Social Situation of Honen’s Times

Honen lived in one of the most turbulent times in Japanese history. It was the transition period from the age of aristocracy to the age of warriors. Wars and uprisings frequently occurred. And, to make the matter worse, there were frequent natural disasters such as earthquakes, fires, epidemics and famines. The idea of mappo (末法), the Buddhist Dark Age, filled the minds of many people with dark thoughts. The pessimism in the air in this period is reflected in several books from the time, such as the Heike Monogatari and Kamo-no-chomei’s Hojoki.

Out of fear of going to hell, Imperial family members and court nobles made offerings to the Buddhist temples and studied profound Buddhist scriptures. Sometimes large buildings and gardens were built to represent the idea of the Buddhist Pure Land on earth. (One of the noted examples of this is the construction of the Phoenix Hall at Byodo-in Temple in Uji, Kyoto, in 1053.) But most of the common people in Japan, who were often poor and illiterate in those days, seemed to be excluded from entering the Buddhist paradise after death.

Honen’s Teachings

It was under those circumstances that Honen appeared in front of the people in Kyoto in 1175 and began preaching. He was determined to do so after about 30 years of studying and practicing at Enryaku-ji Temple on Mt. Hiei. He said to the masses that everyone can be saved into the Buddhist Pure Land, without any distinction between the rich and the poor, or the good and the evil, as long as one repeats the words “Namu Amida Butsu” with all one’s heart. His teachings, with their ease of practice, were followed by many people in every walk of life.

Opposition from the Old Buddhist Schools

Studies suggest that by the time Honen turned 70, the number of his followers in Kyoto exceeded 30,000. But as his popularity grew, the established Buddhist powers gradually became dissatisfied and hostile towards him. In 1204, the monks of Mt. Hiei gathered in front of the Main Hall of Enryaku-ji and implored the head priest to stop Honen’s way of nembutsu, saying that it was a heresy and Honen’s disciples were speaking ill of other sects. And in 1205, Jokei, high priest at Kofuku-ji Temple in Nara, sent to the Imperial court a document, now known as the Kofuku-ji Petition, listing the nine “errors” in the teachings of Honen.

The Jogen Persecution and Anraku-ji Temple

The strongest blow against Honen came in 1207. Around that time, Honen’s disciples, Juren and Anraku, were often holding nembutsu services at Shishigatani (around present-day Honen-in). They chanted nembutsu to a melody, in the style called rokuji raisan (六時礼賛), with their reputed beautiful voices. And Juren, in particular, was described by Yoshida Kenko in his Tsurezuregusa (Essays in Idleness) as “the handsomest monk in Japan.”

One day, two young ladies of the court serving the Emperor Emeritus Gotoba attended a service held by the two monks during Gotoba’s absence. The ladies, who were still teens then, were so impressed that they renounced the world and became nuns. Hearing of the incident, Gotoba became furious. He immediately embarked on a terrible suppression of Honen’s sect, now known as the Jogen (Ken’ei) Persecution. He had the two monks executed in a cruel way and sent Honen into exile to the island of Shikoku. Nembutsu was completely banned. And Honen’s Pure Land movement entered a period of stagnation for several years to come.

Anraku-ji Buddhist Temple, which stands very close to Honen-in, was originally founded in memory of the two young monks who died tragically. Now, in the main hall there are images of Juren and Anraku as well as those of the two court ladies. And in the precincts stands four memorial towers for each of the four people. The temple is open to the public only on limited days in spring and autumn, as well as on July 25 when the annual Squash Memorial Dedication is held there. This temple is really one of the hidden gems in Kyoto in the true sense of the word.

Path of Philosophy and Lake Biwa Canal

The Path of Philosophy (Philosopher’s Walk) was so named because a philosopher, Nishida Kitaro (1870-1945), used to take walks there. This walkway stretches 1.5 km (0.9 mi.) between Ginkaku-ji and Eikan-do along an irrigation channel, which is a branch of the Lake Biwa Canal. Many people say that the best time to visit there is in the beginning of April when the cherry trees along the path are in full bloom, but autumn is also beautiful. If you go there early in the morning, you probably won’t come across many people walking there even in the high seasons.

The Lake Biwa Canal is the network of waterways bringing the water of Lake Biwa (in Shiga Prefecture) to the city of Kyoto. Under the initiative of Kitagaki Kunimichi, then governor of Kyoto Prefecture, the construction of the principal canal was completed in April 1890 (it expanded further in later years). It was a large-scale project using an enormous amount of money and about 4 million workers in total. The canal water was (and still is) used by Kyoto citizens for various purposes, including drinking, irrigation and industry. Until the 1940s, the canal was also used for freight transportation.

Some of the locations associated with the Lake Biwa Canal are popular tourist landmarks. Aside from the above-mentioned Path of Philosophy, there is the famous Nanzen-ji aqueduct in the precincts of Nanzen-ji Temple. Constructed in 1888, it spans 93m in length, with a width of 4m and a height of 14m. With its old red bricks and arches, the aqueduct has a quaint air, giving the temple an exotic atmosphere we can’t see in any other temple in Kyoto. As part of the Lake Biwa Canal, the water flowing across the top of the structure is still regularly being used today.

Keage Incline

Stand at the Nanzenjimae intersection, and look down below. You can see a narrow channel in which water is rapidly flowing and a seemingly abandoned railway track. The channel is also part of the Lake Biwa Canal, and the railway track is the legacy of the former boat transportation system, commonly called “the Keage Incline.” Since this area had the steepest incline in the entire waterway, the wooden boat that carried cargo (and sometimes people) was not able to pass here.

So, they built a 600m railway track on this inclined plane in 1890. And a boat was hoisted onto a flat car and traveled on the tracks. The power to move the system was generated by utilizing the movement of the canal water at the Japan’s first business-use hydroelectric power station completed nearby in 1891. It was the electricity from the same plant that provided households in Kyoto with electric lighting and ran the Japan’s first tram system (the Kyoto Electric Railway) in 1895.

Konchi-in Temple

Konchi-in is one of the several tatchu (塔頭, or sub-temples) of Nanzen-ji Temple. Technically, Konchi-in is not on the same grounds with Nanzen-ji, but adjacent to it, across a paved road. Perhaps that is why, even when the precincts of Nanzen-ji are crowded with sightseers, there are slightly less visitors here.

Konchi-in was originally founded around 1400 in Kyoto’s Kitayama area. But the temple’s third abbot, Ishin Suden, relocated it to the present location in Higashiyama around 1600 and incorporated it into Nanzen-ji. Suden was also an advisor to the shogun Tokugawa Ieyasu (1542-1616) and involved in several important policies under the Edo samurai government. He was nicknamed the “minister in black robes,” the robes indicating a monk participating in politics.

Toshogu at Konchi-in

It is because of this relationship with Ieyasu that there is a Toshogu shrine standing on the grounds of Konchi-in. The Toshogu shrine is a mausoleum enshrining Ieyasu as a deity. Among many Toshogu shrines in Japan, there are only three that Ieyasu himself ordered to be built according to his will: Nikko Toshogu in Tochigi Prefecture (in the Kanto Region), Kunozan Toshogu in Shizuoka Prefecture (in the Chubu Region), and this one at Konchi-in. Suden built this structure in 1628, with a lock of Ieyasu’s hair and personal Buddha statue placed in it.

Cultural Assets of Konchi-in

The temple also has a number of Japan’s important cultural properties, including a painting by Hasegawa Tohaku titled “Monkey Grasping for the Moon.” This work was painted on a fusuma sliding screen in the small shoin (reception room) in the Main Hall. In this work, a monkey trying to catch the reflection of the moon is skillfully depicted.

The small tearoom adjacent to the shoin is called Hasso-no-seki (Tearoom with Eight Windows). This is said to have been designed in 1627 by Kobori Enshu, a renowned tea master and landscape artist at that time. It is considered to be one of the three great tearooms in Kyoto. Visitors to the temple can appreciate these cultural assets for an additional fee. (If you wish to view these special rooms, advanced reservation is recommended.)

Crane and Turtle Garden

But perhaps few people would argue that the highlight of Konchi-in is its karesansui (dry landscape) zen garden that stretches to the south of the Hojo (Main Hall). The garden is commonly called “Crane and Turtle Garden” and has been designated by the nation as a Special Scenic Spot. Suden commissioned the aforementioned Kobori Enshu to build this garden. It is said that Suden ordered the construction of this garden for the purpose of receiving Tokugawa’s third shogun, Iemitsu, here.

While there are many gardens, large and small, across Japan that are “said to have been designed” by Kobori Enshu, most of them don’t have firm evidence of that. But this garden is one of a few exceptions (or maybe the only one exception) because Suden’s own letters and diaries clearly refer to his association with Enshu in building this garden. The garden was completed in 1632.

One of the features of this garden is the wide expanse of white sand, which is said to represent the ocean. And at the back of it is a small hill covered with well-pruned green shrubberies representing shinzan-yukoku (深山幽谷, deep mountains and dark valleys). One may notice that almost all the plants in this garden have green leaves even in the middle of autumn. This selection of evergreen trees is intentional. It comes from the idea that the garden for welcoming the shogun should not wither or wane (as it is a bad omen). After all, this is a “garden of celebration.”

If you sit in the hojo and look at the garden, you may wonder what the large rectangular stone placed at the center of the rock formation signifies. It is called yohai-seki (遥拝石). Yohai means “praying from a distance” in Japanese. This stone was placed here so that people could worship towards the Toshogu shrine located in the same compound. But this does not mean someone actually steps onto the garden and prays on this stone. A Japanese zen garden is basically designed for appreciating from a distance. So, this stone is a kind of symbol of an altar and was placed there as part of the garden design.

This yohai-seki is sandwiched between two stone groupings. The one on the right is called Crane Island, with a long stone jutting out portraying the crane’s head. And the one on the left is Turtle Island, with the conspicuous kito-seki (亀頭石) representing the turtle’s head. In the feudal era, both the crane and the turtle were considered to be the symbols of longevity and prosperity, and their motif is often seen in Japanese gardens from the feudal era.

Behind the yohai-seki is a group of three large stones (although they can’t be seen distinctly from the Hojo because of the distance). It is called the Buddhist Triad Stones and is said to signify Mt. Horai (Mt. Penglai), where, according to a Chinese legend, immortals live.

Getting There (English Map)

To get to Honen-in from JR Kyoto Station, take the Kyoto City Bus route No.5 bound for Iwakura. Get off at “Jodo-ji” and walk for ten minutes towards the mountains. If you use a taxi, it takes about 20 minutes from JR Kyoto Station and about 12 minutes from Shijo-dori Street at Gion.

Other Photos

Places Nearby

With about 3,000 maple trees in its precincts, autumn in Eikan-do (Zenrin-ji Temple) was praised by many distinguished poets and novelists, including Akiko Yosano and Jun’ichiro Tanizaki. In addition, some of the temple’s treasures are shown to the public in November.

Besides Konchi-in I talked about above, Nanzen-ji has some attractive tatchu in its precincts. In particular, Nanzen-in and Tenju-an are popular with their beautiful gardens. And Nanzen-ji’s own “Hojo garden,” which is commonly called the Leaping Tiger Garden, is also well-known. Speaking of the temple’s structures, you can climb to the top floor of the enormous Sanmon Gate, which commands a magnificent view of Kyoto City, for a fee of 600 yen for adults (as of 2021).

Conclusion

The Higashiyama area in Kyoto has many interesting sights, other than the ones I introduced in this post. I hope I can talk about them another day. If you are thinking about traveling through Eastern Kyoto, please send a message through the Rate/Contact page of this website.

Photographs: taken at a couple of places in Eastern Kyoto,

by Koji Ikuma, with a Fujifilm X-T1 and a P. Angenieux Paris 15mm f1.3 lens.

Outbound Links (New Window)