Overview

The Hakkoda Mountain range, or “Hakkoda Mountains,” occupies the south-central part of Aomori Prefecture in the Tohoku Region. (Aomori is the northernmost prefecture of Honshu, which is Japan’s main island.) It is a volcanic area that consists of eighteen different peaks, though people sometimes call it Hakkoda-san (Mount Hakkoda) as if it were one single peak. Kyuya Fukada, a famous mountaineer and writer, also referred to them collectively as Mount Hakkoda in his influential One Hundred Mountains of Japan published in 1964.

The mountain range is roughly divided into two different volcanic groups. The northern group has ten peaks, including Mt. Odake, which is Hakkoda’s highest peak with an elevation of 1,585 meters. The southern group, which is geologically older than its northern counterpart, contains ten peaks with 1,516m Mt. Kushigamine as the highest. Japan National Route 103, which connects Aomori City to Towada City, runs between these two groups.

Most of the tourist attractions, such as climbing trails, an aerial lift, ski resorts and hot spring resorts (onsen), are concentrated in and around the northern group. On the other hand, the peaks in the southern group are not considered to be very suitable to inexperienced climbers and hikers mainly because the paths are not well maintained, with vegetation hampering the ascent (although this situation helps to preserve the nature there).

Speaking of the name Hakkoda, The Shinsen Mutsukoku-ki, Aomori’s local history compiled in 1876, states that hakko (八甲, eight shields or armors) refers to the eight (in this case, “several”) peaks in the mountain range, and da (田, fields), in this case, indicates wetlands. Many peaks in Hakkoda have beautiful conical shapes, and to me, it looks like a collection of tortoise shells. And a number of high-altitude marshes, with their wild alpine plants, dot the area, attracting many visitors. Today, expansive areas in the Hakkoda Mountain range are preserved and protected as part of Towada-Hachimantai National Park.

Hakkoda Ropeway

One of the most popular attractions in the Hakkoda Mountains is the Hakkoda Ropeway, an aerial lift line which carries visitors straight to the summit area of Mt. Tamoyachi (one of the peaks in the northern volcanic group) in ten minutes. With a capacity of 101 and total travel length of 2,459 meters, the lift operates all year round. During a ride, you can enjoy the panoramic views of the mountain range and its surroundings.

Also, from the lift window, you can observe the vegetation cover changing as you rise higher in the cable car. When the lift starts at about 660 meters above sea level, you see the deciduous broad-leaf forest consisting mainly of buna (Japanese Siebold’s beech) and maple. Then, from 1,000 meters above sea level, the subalpine zone begins. The trees that dominate in this zone is the type called Maries’ fir, which is locally known by the name of Aomori Todomatsu. This tree is a symbol of Aomori City.

About a 10-minute ride on a cable car takes you to the Summit Park Station. There is a nature walking trail crossing the summit area. You can see more than ten ponds and marshes in this area. Since the trail is shaped like a figure eight that resembles a gourd, it is commonly called the Hakkoda Gourd Line. If you walk about 30 minutes on the trail, you will reach the summit of Mt. Tamoyachi at 1,324 meters. On the way to the summit, you can observe several varieties of alpine plants and marsh plants. The paths are not so steep on this walking trail, so it is suitable for everyone, young and old alike.

At the end of this Gourd Line, a “real” climbing path begins. You can first climb Mt. Akakura (1,548m), and by walking along the mountain ridge via the top of Mt. Idodake (1,548m), you can finally reach the summit of Mt. Odake, Hakkoda’s highest peak. It takes about two hours from the Summit Park Station to the top of Mt. Odake. It is often said that this climbing route doesn’t require professional climbing skills, but you still need to be equipped with the appropriate mountain gear, including trekking shoes and warm clothes. The best climbing season is from June to October. Climbing in winter months is not encouraged because of heavy snow, severe cold, and avalanches.

Located in a volcanic zone, the Hakkoda area has several remote, but nationally famous, hot springs where people come to visit by car even all the way from the Kansai Region. Among them, the Sukayu Onsen resort (>>See the top photo on this page) is the most well-known. I will talk about it in the latter part of this post.

Jogakura Bridge

Jogakura Bridge is another popular tourist attraction of Hakkoda. With a total length of 360 meters and height of 120 meters, this is the largest “upper-road type” arch bridge in Japan. From the bridge, you can enjoy the panoramic views of the Hakkoda mountains, Mount Iwaki (30 km to the west), and even the city of Aomori in the far distance. If you look down, you can see the magnificent view of Jogakura Gorge. In autumn when the maple leaves turn crimson and the buna leaves turn yellow, the scenery from the bridge is spectacular. There are parking lots on both sides of the bridge which can accommodate some fifty cars.

The upper Tsutsumi River running at the bottom of the valley is called the Arakawa by local residents. Flowing through the volcanic zone, the river water is highly acidic and no fish can live in this part of the river. There used to be a hiking trail that went down the valley to the river. But this route is currently closed because it is considered dangerous.

Two kilometers away from Jogakura Bridge lies Hotel Jogakura. Surrounded by dense buna forests, this hotel is relatively new and has a stylish Scandinavian-style exterior. There is a natural hot spring within this hotel, called Jogakura Onsen. The facility doesn’t have mixed gender bathing, so men and women use different baths. Taking a dip in its outdoor bath in the middle of Mother Nature is a superb experience.

Happy Anaguma

It was also near Hotel Jogakura that I encountered Japanese badgers (anaguma) one September day. I make it a rule to take a walk whenever I have a chance. (That is because of my beer belly. I am hoping it will be gone someday.) That day, after parking my car near the hotel, I began to walk down the Aomori Prefectural Road 122, which is a narrow, unpaved path surrounded by dense woods. I came to a meadow and saw a few small furry animals moving there. They were not cats or racoon dogs but anaguma (Japanese badgers).

I thought their eyesight was not very good because I was easily able to get closer to them and take photos. Japanese badgers live on most of Japan’s land except Hokkaido, but we seldom see them because they are timid, nocturnal animals. They are sometimes called mujina in old Japanese folktales. In these tales, they often turn into humans and deceive people. Anyway, I haven’t seen Japanese badgers as happy as this before or since. Maybe it was partly because they have less threats here as this area is protected by law.

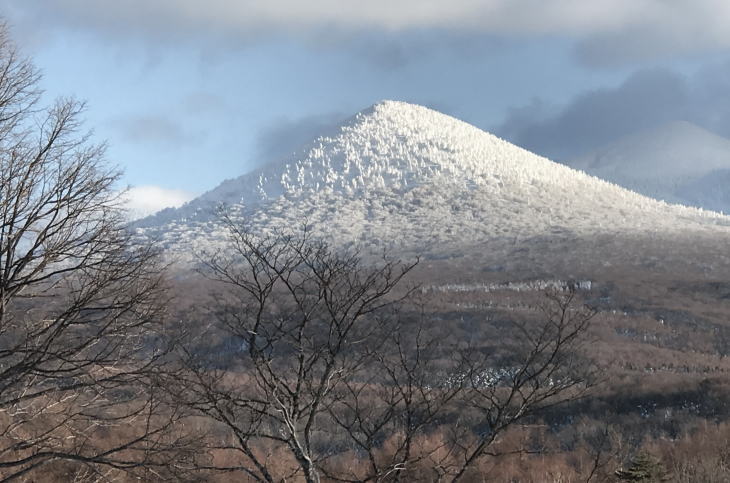

Meeting Snow Monsters

The area in and around the Hakkoda Mountain range is one of the coldest and snowiest regions in Japan. In Aomori Prefecture, generally speaking, the more southern you go, the colder it becomes. So, the winter temperatures in the Hakkoda area are generally cooler than those of the city of Aomori. And Sukayu, which is located southwest of the Hakkoda Mountain range, has the snow accumulation record of 5.66 meters since the Automated Meteorological Data Acquisition System (AMeDAS) was introduced nationwide in 1974.

The powdery quality of the snow in Hakkoda is highly praised among skiers and snowboarders all around the world. It is often said that the snow in Hakkoda resembles that of the famous ski resorts in Hokkaido. Also, winter in Hakkoda offers us another noted attraction: the so-called “snow monsters.”

In winter, clouds containing supercooled water droplets come into contact with Maries’ fir (Aomori Todomatsu) trees in the upper part of the Hakkoda mountains. Consequently, fragile, needle-like ice is formed in the branches of the trees. This milky-white type of ice is called “rime.” Then, as the further snow falls, a kind of chemical reaction called “sintering”(焼結) occurs between the snow and rime ice. Huge snow blocks are formed by this reaction, and as they grow further, the surfaces of the trees are completely covered with snow blocks. This huge concentration of snow is called a snow monster.

The best time for seeing snow monsters is in January and February. In spring, especially on days with strong sunshine, they are said to collapse one by one. If you get close to one of the monsters, please watch your step because the surface around each monster is often unstable with several depressions.

Also, please don’t forget the departure time of the last cable car returning to the base. If you are equipped with skis or snowboards, it doesn’t matter, because you can descend on your own. But if you don’t have this snow gear and you miss the last car, you could be stranded at the mountain top with these eerie snow monsters.

Hakkoda Mountains Incident

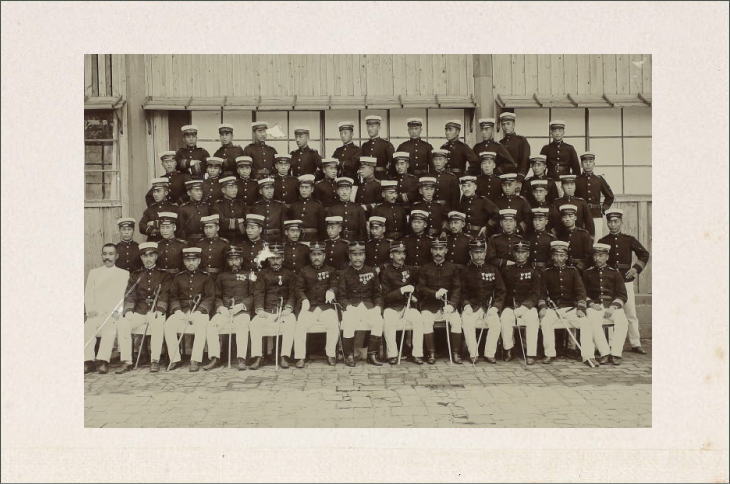

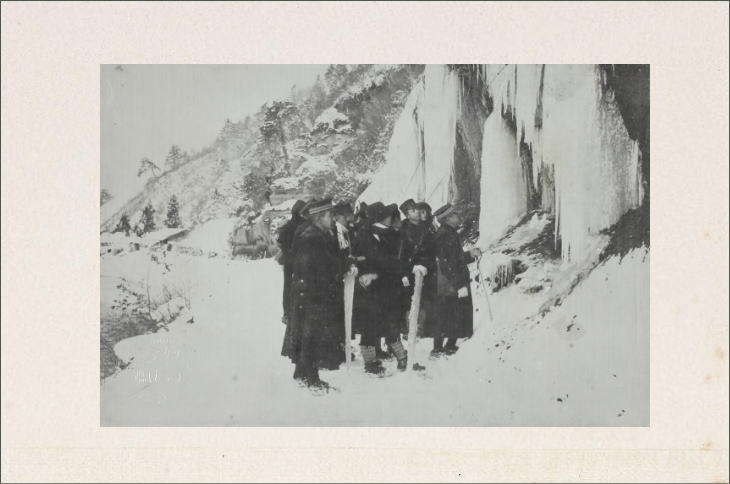

Here we should look at a dark moment in history. The Hakkoda Mountains Incident that occurred in January 1902 is still one of the worst disasters in the history of mountaineering. Two infantry regiments of the Imperial Japanese Army set out to cross the snowy Hakkoda Mountains from opposite directions. The Fifth Infantry Regiment stationed in Aomori headed for Hakkoda from the north, while the 31st Infantry Regiment stationed in Hirosaki first went east, and passing the south side of the mountain range, proceeded toward the Hakkoda area. It was military training in preparation for the Russo-Japanese War which seemed imminent at that time (and it actually broke out two years later in 1904).

But, before reaching their first-night destination, which was the Tashiro Hot Spring, the Aomori Regiment was stuck in a severe blizzard, having no choice but to bivouac. The weather showed no sign of improvement for the next couple of days. They lost their way and wandered around the northern slope of the Hakkoda Mountains. As a result, 199 out of 210 soldiers were frozen to death. On the other hand, the Hirosaki Regiment was cautious (for example, they hired local guides to lead them through some dangerous sections) and successfully completed their journey with no fatalities.

To this day, the cause of the Aomori Regiment’s disaster has been argued and examined from various angles. Many people agree that their chain of command was disordered. Captain Bunkichi Kan’nari was supposed to be the leader of the group. But Major Shin Yamaguchi, who was Kan’nari’s superior, was also in the group (probably, just to observe them with no actual right to take command). It seems that by the night of the first day, Yamaguchi somehow began to assert himself and made several decisions that in hindsight turned out to be disastrous. Some people also criticize Kan’nari for his reluctance to take a stand against his superior because he obviously sensed there was something wrong in Yamaguchi’s decision-making but did nothing.

The YouTube clip below shows a couple of scenes from 1977 Japanese movie Mount Hakkoda. It is a blockbuster movie, partly based on the disaster. (The original novel was Jiro Nitta’s Death March on Mount Hakkoda published in 1971.) It was actually filmed in and around the Hakkoda Mountains over a period of three years. In this clip, the Hirosaki 31st Infantry Regiment, led by a local mountain guide, walks across the snowy fields and over the hills. The last scene of this clip is cited by some as the finest on-screen moments of two legends of Japanese cinema: Ken Takakura and Kumiko Akiyoshi.

❖There is sound. Please be sure to wear your headphone.

Michinoku Fukazawa Onsen is a remote, rustic, small-scale hot spring facility located on the northern slope of the Hakkoda Mountain range. This is an alkaline hot spring which is supposedly good for neuralgia, arthralgia and poor blood circulation. Surrounded by buna forests, the scenery as seen from its outdoor bath is superb.

But bathing there sometimes gives me uneasy feeling because this place is very close to Tashiro Hot Spring, the destination the Aomori Fifth Regiment struggled in vain to reach in 1902. Although currently not in use, Tashiro Hot Spring back then is said to have been a very small-size outdoor facility run by an elderly husband and wife, which was similar in appearance to this Fukazawa Onsen.

Sukayu Onsen

Sukayu Onsen is a hot spring resort located in the southwest of the Hakkoda Mountain range. The origin of the facility dates back some 300 years. When you arrive here and get out of your car, you will immediately find that the smell of sulfur is already floating in the air. The onsen water here contains acidic sulfate and is said to be effective for nerve pain, joint pain, and intestinal diseases. The sulfur smell sticks to your skin and remains with you for a long time after you leave the bath. But I can assure you the bath water will definitely relieve you of some of your fatigue after a day of hard work.

Sukayu Onsen was designated as the People’s Recreation Hot Spring in 1954 with the other two onsen areas: Nikko Yumoto in Tochigi Prefecture and Shiman in Gunma Prefecture. These were first such designation given to any hot spring resort. The designation as PRHS is given by the Minister of the Environment to facilities which meet various standards, including the healing quality of onsen water, enough amount of gushing spring, reasonable prices, and so on.

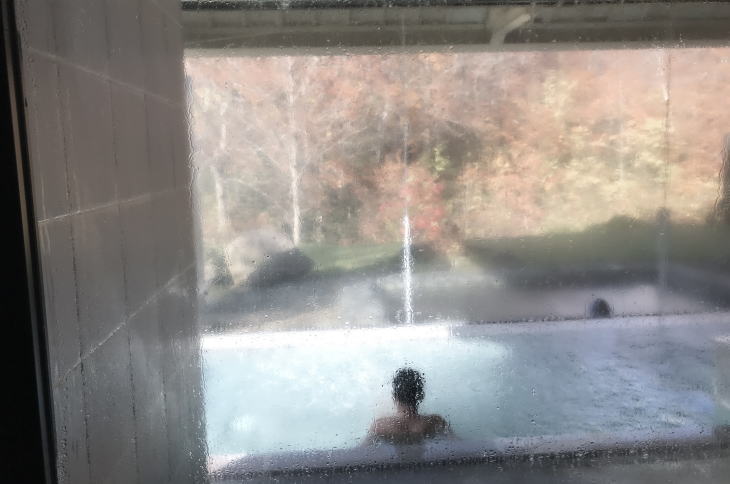

Sukayu Onsen offers a couple of different baths (although the water quality of these baths is more or less the same). Among them, the most famous is the massive bath made of beech wood, called sen’nin-boro, or the “bath of thousand bathers.” This bath is known as one of a few konyoku (混浴, mixed gender nudity bathing) baths still remaining in Japan.

Traditional konyoku culture in Japan and its moral right and wrong has been a controversial issue for many years. Back in the mid-19th century, a number of foreign visitors to Japan, including the people in the Commodore Matthew Perry’s expeditions, are said to have frowned when they saw naked men and women mingling in the same baths. And they say that seeing these scenes, none other than Perry himself said, “I question the moral sense of the people in this country.”

Worried that the custom of mixed bathing would not necessarily give a good impression to Western nations, the Meiji government banned konyoku at public bathhouses in Tokyo in 1869 and the ban eventually spread to other areas in the country. But in fact, it seemed that this regulation was not that strictly observed by the populace and bathhouses at that time. So, the government had to issue similar bans again and again.

Today, I understand it requires courage for women to share the same bath with the opposite sex at Sukayu Onsen. But I hope they will summon up a courage and take the plunge. I have soaked in the sen’nin-buro several times, and I can say that most of the time, I was not able to recognize who was sitting next to me in the bath because the air in the room were filled with steam (in winter especially) and the bath water was milky-white. I didn’t see nothing, most of the time.

Volcanic Activities

Although the Hakkoda Mountains have not erupted in recorded history, the mountains range (Mt. Odake in particular) is now officially categorized as an active volcano. Hot springs are, of course, the signs of geothermal activities. Also, a couple of fatal incidents occurred during the last thirty years. In June 2010, for example, a junior high school girl died and her relatives were hospitalized after they (possibly) inhaled toxic volcanic gas on a mountain near Sukayu Onsen. They were picking edible wild plants, probably deviating from regular climbing trails.

Today, the Japan Meteorological Agency is paying a special attention to two particular areas in the Hakkoda Mountains. One is the area around the craters of Mt. Odake and the other is Jigokunuma Pond (Jigoku is ‘hell’ in Japanese), a ten-minute walk from Sukayu Onsen. In these areas, multiple noticeable earthquakes were monitored in recent years. Although researchers say that these tremors are not signs of coming eruptions or big earthquakes, hikers may need to keep these hazards in mind when they visit the Hakkoda Mountains.

Getting There

To get to the Hakkoda Ropeway station by car from the city of Aomori, please take Japan National Route 103 all the way to the north. It’s an about 40-minute drive. Sukayu Onsen is also located on the same route as the Ropeway station (about another 10-minute drive by car from the Ropeway station). When you take a return bus to the city in high season (especially in mid-October), please be careful because sometimes there are so many passengers depending on the time of day.

Other Photos

❖There is sound. Please be sure to wear your headphone.

Conclusion & Contact

The conclusion is I like the Hakkoda Mountains. Like the hot springs there. Like the rich variety of its nature and wildlife there. Unfortunately, I couldn’t introduce all the charms of the Hakkoda Mountains in this post. Several places I didn’t mention include Tashirotai Wetlands, Tsuta-no-Nananuma Pond, Suiren’numa Pond, Kuzu Onsen, and Sarukura Onsen, among others. Also, I didn’t mention some of the legendary names associated with the Hakkoda Mountains: the names of people such as Shiko Munakata (a hanga artist with international fame) and Tatsugoro Shikanai (a legendary mountain guide clad in a military uniform, who fought in the Russo-Japanese War). I would like to talk about these things and people at another opportunity. If you are interested in visiting the Hakkoda area, please send a message through the Rate/Contact page of this website.

Photographs by T. Terada, unless otherwise noted. (Featured photo: The wooden building of Sukayu Onsen at twilight time in mid-February, with Mt. Odake in the background.)

Outbound Links (New Window)