Overview of Hamamatsu

Shizuoka Prefecture (in the Chubu Region) is located on the Pacific coast, roughly halfway across Honshu, Japan’s main island. It is a long prefecture east-west. This prefecture is usually divided into three regions, western, central, and eastern, but this division is based on the old provinces of the Edo Period (1603-1867). After the Meiji Restoration, these three provinces were combined to form Shizuoka Prefecture. For this reason, it is said that there are considerable differences, for example, between the western and central regions of Shizuoka in terms of major industries and the temperament of the people.

The western region of Shizuoka Prefecture was formerly known as Totomi or Enshu, and its central city is Hamamatsu. (Incidentally, the name “Enshu” is still widely used today.) As of 2024, Hamamatsu is the largest city in Shizuoka Prefecture in terms of both population and area. It is primarily an industrial city, and has developed through industries such as musical instruments, motorcycles, and automobiles. In addition, the city is blessed with quite a few tourist resources, which include Lake Hamana and the Kanzanji Onsen hot spring resort in the suburbs. Lake Hamana was originally a freshwater lake, but a major earthquake in 1498 connected it to the open sea and turned it into a brackish lake. This has resulted in a rich biodiversity and a treasure trove of food ingredients.

Also, the Hamamatsu Kite Festival in early May attracts many visitors. This festival does not have any particular religious background. It is a “citizen’s festival” held to celebrate the birth of a newborn baby of each household. In recent years, more than 150 towns in Hamamatsu have participated, and during the day, kites from each town, each with their own unique design, fly in the sky all at once. When a kite battle is held at the signal of the bugle, hundreds of people get mixed up, and the venue becomes like a battlefield. (One of the reasons why the bugle is used is said to be that, until just before the outbreak of the Pacific War, the festival’s venue was the Wajiyama parade ground of the 6th Infantry Regiment of the Imperial Japanese Army.) And in the evening, many decorated festival floats slowly make their way through Hamamatsu city center in front of crowds of spectators.

❖There is sound. Please be sure to wear your headphone.

There is a phrase often cited to describe the temperament of the people of Enshu. That is “Yaramaika,” an Enshu dialect for “Let’s give it a try.” Reflecting this positive disposition, perhaps, many companies started businesses in Enshu and have since grown into global corporations. Honda Motor Co., Ltd. and Suzuki Motor Corporation, both of which are major automobile/motorcycle manufactures, originally started out as small local factories in Hamamatsu, and the latter still has its headquarters there today. Toyota Motor Corporation is strongly associated with Aichi Prefecture, but the birthplace of Sakichi Toyoda, the founder of Toyota Industries, is in what is now Kosai City (the city west of Hamamatsu). So, the company’s roots actually lie in Enshu.

Speaking of the food, Hamamatsu has two foods that are famous nationwide: Gyoza dumplings and Unagi (eels) dishes. The former is called “Hamamatsu’s soul food” and the latter is often described as “the king of Hamamatsu gourmet,” and it is worth noting that both are extremely nutritious foods. In addition to these two foods, soft-shelled turtles (“suppon”) and oysters have long been cultivated around Lake Hamana, and there is no doubt that these nutritious foods have supported the powerful and energetic people who embody Hamamatsu’s “Yaramaika spirit.” In this post, I would like to focus, in particular, on the “Hamamatsu eels” in Lake Hamana.

Eels from Lake Hamana, and Miscellaneous Stories about Eels

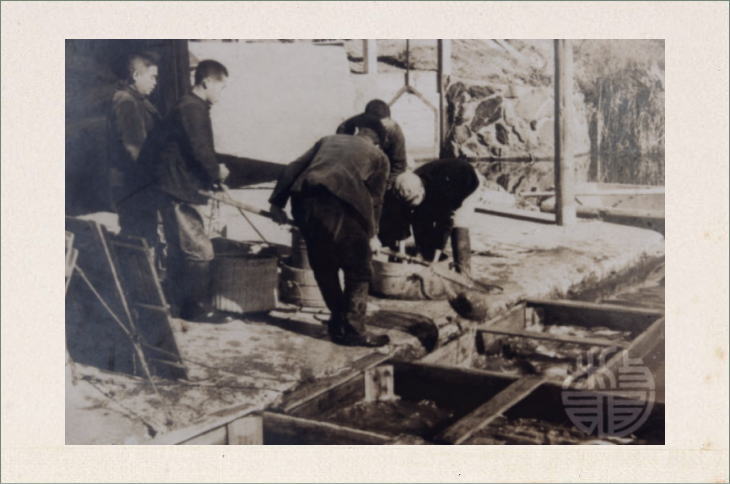

Lake Hamana is the birthplace of eel farming in Japan. In 1887, Hattori Kurajiro, a river fish merchant from Fukagawa, Tokyo, saw the lake from the train window while on a business trip to Kansai and thought, “This is the best place for aquaculture.” He is said to have actually got off the train and walked around the area. Then, in 1900, he acquired land in what is now the Fukiage district near JR Maisaka Station and began farming soft-shelled turtles first, and then eels, which led to the boom of eel farming along the shores of Lake Hamana. Kurajiro established the Hattori-Nakamura Suppon Farm in 1914. And, over the years, the “Hamamatsu style” eel farming method gradually spread to other prefectures.

It is said that the reasons for the success of eel farming in Western Shizuoka included the warm climate (with an average annual temperature of 15 degrees Celsius), the large catches of glass eels in Lake Hamana (The lake is connected to the Pacific Ocean, so fish from the open ocean flow into the lake.), and the presence of thriving silkworm farming areas nearby, which made it easy to obtain silkworm pupae, which were often used in early eel farming to feed the baby eels. Another reason was that Hamamatsu is located almost halfway between Tokyo and Osaka (Kyoto), and with the opening of the Tokaido Line in 1889, it became possible to ship eels by rail to major eel-consuming areas. Shizuoka Prefecture’s farmed eel production peaked in the late 1960s, when eels from Shizuoka Prefecture accounted for about 70% of the national production.

Recently, the yield of farmed eels in Lake Hamana has been on the decline. Looking at the eel production by prefecture, Shizuoka Prefecture’s eel production is lower than that of Kagoshima and Miyazaki in Kyushu, and Aichi Prefecture to the west. Furthermore, eels that have been grilled and frozen in China or Taiwan are being imported into Japan in large quantities, and there are even chain restaurants that use these imported eels to serve unadon (eel rice bowls) at reasonable prices. Despite these difficult circumstances, many people in Japan still associate eels with Lake Hamana in Hamamatsu. The reason why the “Lake Hamana brand” of farmed eels is still going strong is probably related to the history I mentioned in the paragraph above.

Also, it seems to be true that the taste of locally farmed eels eaten around Lake Hamana is a little different from eels from other regions. In fact, there are many long-established eel restaurants in Hamamatsu that use their own hiden no tare (or “secret sauce”) to preserve the traditional taste, and many tourists say that, because eel is a luxury ingredient, they want to try it at a famous restaurant in Hamamatsu, the original Eel Kingdom. Uchiyama Mitsuharu, president of the Lake Hamana Fish Farming Cooperative, once said in a newspaper interview, “Lake Hamana eels are high quality because they are raised in good quality water.” In order to protect this “Lake Hamana brand,” Lake Hamana eels are now defined as “eels that have been raised in the Lake Hamana area (Hamamatsu City and Kosai City) for more than 60% of their life.”

Japanese people have a long history of eating eels. Eel bones have been excavated from Jomon Period (13,000BCE-900BCE) ruins, and the Man’yoshu, Japan’s oldest collection of waka poetry, compiled in the 8th century, contains a waka that says, “Catch and eat eels because they’re effective for summer fatigue.” The Japanese custom of eating eel on Doyo no Ushi no Hi (the Midsummer Day of the Ox, which is based on the twelve signs of the Chinese zodiac and often falls at the end of July or the beginning of August) to gain stamina is said to have begun in the mid-Edo period, when Hiraga Gennai (1728-1780), a renowned versatile genius, encouraged it.

Eels are known to be rich in various nutrients, especially vitamin A, making them ideal for surviving the hot and humid Japanese summer. In his 1998 book “Unagi of Lake Hamana, Past and Present,” Yasuji Aiso, then president of Aikane Shoten, wrote that one eel alone contains enough nutrients to sustain one’s energy for the day, citing the story of a man who ate so much eel for lunch that he wasn’t hungry by the evening and had only a beer to get by.

Grew up in Western Shizuoka, I have personally experienced the fatigue-relieving effects of eels, and have had the experience of reaffirming this effect in conversations with other people on several occasions. One story that particularly made an impression on me was a story a friend of mine told me a few years ago about a housewife: She and her husband were invited to a relative’s house and were treated to a large eel feast, but afterwards her husband became too energetic, which caused some problems.

Kabayaki (where eels are butterflied and then basted) has long been the most popular way to prepare eel in Japan. In the Kanto region, the eel is cut open from the back, grilled without sauce (tare, pronounced as “Tar Ray”), then steamed, and then again grilled with tare. In the Kansai region, the eel is cut open from the belly and slowly grilled without steaming. The difference between these two cooking methods also leads to a difference in texture. Hamamatsu is located halfway between Tokyo and Osaka, so restaurants that use the Kanto style and those that cook in the Kansai style coexist in Hamamatsu.

Eels in the West

We Japanese tend to think that Japanese people are the only ones in the world who eat eels, and that the only way to cook eels is as kabayaki, but Mr. William F. O’Connor, a professor in the Department of Business Administration at Asia University, disagrees with this stereotype. He posted about eels in eight parts from September 2 to October 23, 2022 on the blog “Drinking Japan” (link at the bottom of this page), which he co-runs with his son Robin. In the sixth installment of the series, titled “The Eel Abroad, Part 1,” he lists a variety of eel dishes from medieval Europe, citing the name of Calvin W. Schwabe, who is the author of “Unmentionable Cuisine.”

In the same post, he provides the following recipe for Eel Reversed, an obscure eel dish from medieval Europe, with help from Ms. Melitta Weiss Adamson, author of “Food in Medieval Times.”: “Eel Reversed can be seen as a variation on the theme of Unagi no Kabayaki. Like the Japanese dish, the fish is roasted on a spit and basted with a syrup. However, in this case, the skin of one eel is encased in the meat of a large skinned eel. The inner skin is seasoned with grains of paradise and wine or verjuice, and a little saffron and salt.* When the encasement has been completed, the creation is pierced with cloves, pieces of ginger, and pine nuts, after which the skin from the flayed eel is reunited with its body in a slipping-over maneuver.” (*The italics are taken from the book “Culinary Recipes of Medieval England” edited and interpreted by the late Ms. Constance Hieatt.)

Furthermore, in his seventh installment of the series, Professor O’Connor even deviates from the usual theme of his blog (i.e. Japanese beverages and their food pairings) and explores other possibilities for eels beyond just being a food source. He focuses on the fact that eel skin is tanned into a very fine, slightly textured leather that can be used to make luxury goods, and imagines the eel leather garments and accessories sold exclusively for couture consumers in boutiques across the city.

Not Just Unadon and Unaju

In Japan, the most popular eel dish after the standard unadon and unaju may be hitsumabushi. A small wooden tub (hitsu in Japanese) contains about three bowls of cooked rice, on top of which are small pieces of grilled eel (kabayaki). The eater transfers the rice and eel to a small rice bowl with a shamoji rice paddle and eats it. The first bowl is eaten as is, the second bowl is topped with condiments such as wasabi and chopped negi (green onions), and the third bowl is topped with dashi stock or green tea and eaten by shoveling it into the mouth. One of the famous restaurants in Hamamatsu for hitsumabushi is Nakagawaya, located near the Tenryu River. The eels used at this restaurant are from Lake Hamana, and the kabayaki is grilled using the restaurant’s own secret sauce (hiden no tare).

A dish of butterflied eel grilled without sauce (tare) is called unagi no shirayaki, which literally means “white grilled eel.” (On the other hand, eel grilled with tare is called kabayaki.) As there is no sauce, it is said to be a connoisseur’s way of enjoying the natural flavor of the eel. Shirayaki has been popular around Lake Hamana for a long time, and many restaurants offer this dish. Being able to serve delicious shirayaki means that they have confidence in the eel they are using, and behind this lies the pride of Hamamatsu as the original Eel Kingdom. Some people eat it with salt, but wasabi joyu (soy sauce mixed with wasabi paste) is probably the best. Compared to kabayaki, this dish goes very well with alcoholic beverages such as sake and wine.

A lesser known dish made with eel is bokumeshi, a local dish from the Lake Hamana region. Bokumeshi is a mixed rice dish made by combining cooked rice with simmered eel and burdock. In the early days of eel farming, eels that grew too big and fat were called “boku” and were not marketable due to their large bones and thick skin. It is said that at the time, eel farm workers would cut these boku into chunks and mix them with rice to eat as staff meals, and this is the origin of bokumeshi. Since then, it has been eaten by local people mainly as a home-cooked dish, but as the price of eel rose, it is said that the number of households making it gradually decreased. Currently, the number of restaurants in Hamamatsu where you can eat this local dish is very limited.

Unagi Pie Factory

Another eel-related specialty of Hamamatsu is Unagi Pie (Unagipie Pastry). Since its release by Shunkado in 1961, this sweets has been popular among people of all ages, from children to the elderly, and is a staple Hamamatsu souvenir. It is a sweet snack made from wheat flour baked with butter, but the key point is that it contains eel extract, which has made it synonymous with Hamamatsu. The recipe for the sauce spread on the freshly baked pie is a company secret.

The Unagi Pie Factory is an Unagipie Pastry production facility established by Shunkado near Lake Hamana in 2005, where visitors can get a close look at the workers known as “Unagipie artisans” at work. It’s particularly great that from the second floor you can get a panoramic view of the packaging and boxing lines, making you feel like the factory manager. You can also sign up for a guided group tour of the factory, and there is also a well-stocked gift shop on the premises. Currently, the facility is said to be visited by more than 600,000 people from within and outside the prefecture each year, making it a popular tourist spot in the Lake Hamana area.

Which Way Does the Eel Industry Go?

The current method of eel farming in Japan is generally as follows: at first, fishermen catch wild young eels (called “glass eels”) that come to Japan from far south on the Kuroshio Current in winter, which are then purchased by eel farmers, who then raise them in their cultured ponds to grow into adult eels and ship them out. This style is fundamentally not much different from the method used by Hattori Kurajiro 100 years ago in the early days of eel culturing, which is surprising in a way. If it were possible to artificially raise eels from eggs to adulthood (we Japanese often use the term kanzen yoshoku or “full-scale eel farming”), it would lead to various cost reductions, but there are still many mysteries surrounding the biology of eels, and even with modern science and technology, we have not yet reached the stage of Full-scale Eel Farming on a practical level as of 2024.

With the above-mentioned background, the number of glass eels is currently decreasing nationwide, mainly due to overfishing. Since June 2014, the Japanese eel (or Anquilla japonica, which is the eel species that Japanese people have mainly eaten since ancient times) has been designated an “endangered species” by the International Union for Conservation of Nature and Natural Resources (IUCN). These are the main reasons why the prices of unadon at eel restaurants and kabayaki packs at supermarkets have increased in recent years. In order to overcome this situation, research institutes all over Japan are working day and night to study eels, with the aim of realizing the Full-scale Eel Farming.

Currently located near JR Bentenjima Station, Shizuoka Prefecture’s Fisheries and Marine Technology Research Institute, Lake Hamana Branch, was originally established in 1904 with the aim of promoting the development of the prefecture’s fisheries. Since then, it has mainly carried out tests and research on aquaculture. It began research into artificial eel hatching in 1962. In 1974, it became the second facility in the world―following Hokkaido University’s research team in 1973―to achieve artificial eel hatching. And in 1996, the institute successfully hatched 24,000 eels (although all of them died eight days after hatching). As far as records show, the current Emperor of Japan visited the institute twice when he was a child (in 1968 and 1970).

Adjacent to the Technology Research Institute is Ulotto, a small aquarium that opened in 2000. It is said that Lake Hamana is home to more than 400 species of fish and more than 59 species of crustaceans, some of which can be seen alive in Ulotto. In addition, you can learn about the various fishing and aquaculture activities that take place in Lake Hamana, and there is also a wealth of information about eels and eel farming.

As mentioned above, a couple of Japanese research facilities had succeeded in artificially hatching eels by the late 1990s, but the hatched larvae (also known as pre-leptocephali) all died soon after. It was because it was completely unknown at that time what the larvae were eating as they grew. (The most difficult part of raising eels is raising them from 5mm pre-leptocephali to 60mm glass eels.) It wasn’t until a little after 2000 that a major breakthrough was made towards resolving this problem. Katsumi Tsukamoto and his team succeeded in collecting pre-leptocephali in May 2005 in the waters near the Mariana Islands, and then in May 2009 they finally succeeded in collecting fertilized eel eggs near the above-mentioned waters. This led to a dramatic advance in our understanding of the environment in which the larvae grow and what they feed on.

When I participated in a cultured pond tour organized by Tenpo, an eel farmer and restaurant in Hamamatsu, in June 2024, President Yamashita said to me, “Artificially raising baby eels has been a long-time dream of this industry. The problem is, we still don’t know exactly what baby eels feed on in the wild. It’s said that it’s probably “marine snow.” Do you know what marine snow is? There is a phenomenon where organic matter, including dead fish, sinks into the deep sea like falling snow, and this is called marine snow. However, this marine snow cannot be made artificially.” “Still, you are looking forward to the realization of Full-scale Eel Farming, aren’t you?” I asked. “Of course I am. In the past, we were taught at school that it was impossible to farm tuna. However, Kinki University succeeded in artificially farming tuna and has commercialized it. So, I think that in about 20 years, we may be able to eat artificially grown eels.”

Arai Sekisho

Along with Hamamatsu Castle Park, the Arai Barrier (Arai Sekisho) on the western shore of Lake Hamana is a representative historical spot in Western Shizuoka. (Arai has been the name of the area since long time ago.) During the Edo period, the Tokugawa Shogunate established checkpoints in 53 locations across the country to control passers-by in order to protect Edo, but Arai Sekisho is the only one in the country where a building from the Edo period still remains. This makes the checkpoint highly valuable historically, and it was designated a “Special Historic Site” by the government in 1955. The checkpoint was originally established in 1600, but has since been hit by numerous major earthquakes and tsunami, forcing it to be relocated a couple of times. The current building was rebuilt by 1858 after the previous building collapsed in an earthquake in 1854.

The street facing the checkpoint gives a vague feeling of the Tokaido in the late Edo period. In particular, Kinokuniya, located about a five-minute walk west of the checkpoint, was the largest and most important inn in the area at the time, and is now open to the public as a museum. The actual inn was destroyed by fire in 1874, and the current building was rebuilt a little later, but it is a valuable building that still retains the feel of an inn from the Edo period.

Interestingly, a travel diary from that time records that this inn, Kinokuniya, served unagi no kabayaki using a secret sauce (hiden no tare), which was very popular. The jars in which the kabayaki sauce was stored can still be seen at the museum today. Lake Hamana was actually known as an eel producing area long before eel farming began, and an eel appears in Hiroshige’s ukiyo-e work which depicts the Arai post station. (Lake Hamana was already connected to the sea at the time, so it is likely that many wild eels were caught.)

The Shogunate strictly controlled the so-called “incoming guns and outgoing women” at the checkpoints. “Incoming guns” were weapons such as guns brought into Edo. “Outgoing women” were the wives and children of local feudal lords who were trying to escape from Edo. (They were made to live in Edo as hostages.) The Arai Sakisho was notorious for its strict control over women in particular. At this checkpoint, not only “outgoing women” but also “incoming women” heading to Edo needed to show a special women’s pass called Onna Tegata, and many details had to be precisely written on it. Baggage and personal inspections were also thoroughly carried out. For this reason, many women tried to pass through the checkpoint dressed as men, so elderly women called aratame onna (also known as aratame baba, or “inspection hags”) who specialized in gender checks were stationed at the checkpoint.

There are many recorded cases where a woman was not allowed to pass through the Arai Barrier because of incomplete information on her pass. Among them, one interesting anecdote is that of Inoue Tsujo (1660-1738), a female waka poet of the Edo period. Tsujo, the daughter of a samurai from Marugame, Sanuki Province (in the Shikoku region), left her hometown for Edo in November 1681 to serve the mother of Kyogoku Takatoyo, the lord of the province. When she arrived at the Arai Sekisho, she underwent a physical examination by an aratame baba and presented her Onna Tegata, but was not allowed to pass through the checkpoint.

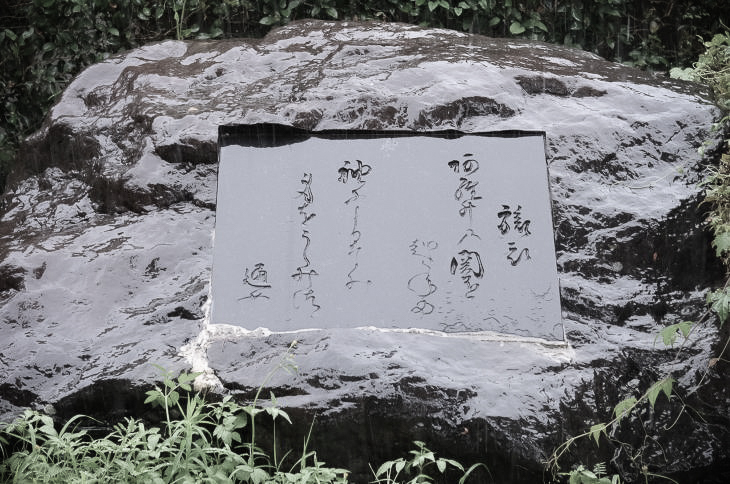

The reason Tsujo was not allowed to pass was because of a minor mistake on the pass she submitted. Because she was wearing a furisode (a long-sleeved kimono worn by young unmarried women), the correct description of her, according to the regulations of the checkpoint, was ko-onna (young woman), but her pass only said onna (woman). Therefore, she sent a messenger to Osaka (which is about 250km west of Arai) to reissue a pass with the correct description, and for the next several days she had to stay at an inn in Arai until the messenger came back. She expressed her feelings while she was waiting in the following waka:

Tabikoromo (My travelling clothes)

Arai no Seki wo koekanete (Preventing me from passing the Arai Sekisho,)

Sode ni yoru nami (The waves come to my sleeves)

Mi wo uramitsutsu (While I have myself to blame.)

In the third line, nami (waves) is a pun on namida (tears), implying that “Tears wet my sleeves.” Anyway, the messenger returned six days later, and as the new Onna Tegata was correct, Tsujo was finally able to pass through the checkpoint. At the time this Tsujo’s case occurred, Arai Sekisho was located about 2km southeast of its current location.

In the very small park now known as Omoto Yashiki, there is a signboard announcing that the first Arai Barrier was near here, as well as a monument bearing Tsujo’s waka. 400 years ago, the town of the original Arai-juku, with over 600 households, spread out around this location (before it was devastated by a heavy rainstorm in 1699), but the neat residential area today bears no trace of that time. However, it was undoubtedly at this location that Tsujo spent several days in anguish and composed her waka.

Getting There

The Arai Barrier is an 8-minute walk from JR Araimachi Station and about 32 minutes by car from JR Hamamatsu Station.

Other Photos

Other Places in Hamamatsu

Located a three-minute walk from JR Hamamatsu Station, ACT CITY Hamamatsu is a complex consisting of a shopping area, a restaurant area, the Main Hall, the Concert Hall, and Okura ACT CITY Hotel Hamamatsu (which is operated directly by Okura Hotels & Resorts). The Act Tower, which forms the core of the complex, is a 212-meter-tall skyscraper, with an observation gallery on the top 45th floor from which a panoramic view of Western Shizuoka can be enjoyed. The building can be easily seen from more than 10 kilometers away, and has been a symbol of Hamamatsu since its completion in 1994.

Hamamatsu is known as a “city of musical instruments and music,” mainly because of the large number of musical instrument manufacturers in the city. In particular, Yamaha Corporation and Kawai Musical Instruments are two world-famous manufacturers that were both founded in Hamamatsu and are still based there today. Also, Hamamatsu International Piano Competition has been held periodically since 1991 at the Act City Concert Hall and Main Hall. To contribute to the advancement of this music culture, Hamamatsu City opened the Hamamatsu Museum of Musical Instruments in ACT CITY Hamamatsu in 1995. The museum regularly displays 1,500 musical instruments collected from around the world.

Conclusion & Contact

In this post, I have mainly focused on the topic of eels in Lake Hamana and introduced some of the interesting spots mainly in the southern part of Hamamatsu City and the southern part of Kosai City. If you are interested in a tour to visit some of them, please send a message through the Rate/Contact page of this website. On the other hand, I was not able to introduce any spots around Kanzanji, a representative tourist spot in Western Shizuoka, or in the northern part of Hamamatsu City. Nor was I able to provide any details about Hamamatsu Castle and the 16 years Tokugawa Ieyasu spent there. I will introduce them in detail on another occasion.

Appendix

Sightseeing Bodies in Western Shizuoka

Hamamatsu and Lake Hamana Tourism Bureau: Hamamatsu and Lake Hamana Tourism Bureau is a public interest corporation approved by the Ministry of Land, Infrastructure, Transport and Tourism. This body was formerly known as the Hamamatsu Convention Bureau. It carries out public interest work, attracting and supporting conventions and promoting tourism. >>English website.

Hamamatsu Tourists Information Center (iN HAMAMATSU.COM): This is located inside JR Hamamatsu Station, and you can get tourist information about Hamamatsu City and the western area of Shizuoka Prefecture. There are English-speaking staff as well as volunteer tourist guides to provide information on Hamamatsu’s tourism, culture, history, etc. >>English website.

Sightseeing & City Promotion Department of the Hamamatsu City Hall: This department mainly handles tasks related to the promotion of tourism and conventions, attracting visitors to the various spots around Lake Hamana. >>Website (Japanese only).

Unagi-related Organizations in Western Shizuoka

The Lake Hamana Fish Farming Cooperative: Established in 1949, this association is primarily involved in the management of eel farming, but also collects and distributes glass eels, purchases feed jointly, and processes and sells adult eels. They also deliver grilled eel to all parts of the country. >>Website (Japanese only).

The “Eel Town” Project Executive Committee: This is a group organized mainly by the younger generation within the Lake Hamana Fish Farming Cooperative (listed above). They have been working with local high schools and organizations to promote Hamamatsu as the “eel town.” They actually hosted the “High School Eel Cooking Contest” four times in the past (as of spring 2024). >>Website (Japanese only).

Shizuoka Prefecture’s Fisheries and Marine Technology Research Institute, Lake Hamana Branch: At this facility, there are 24 thermostatic tanks of various sizes which are mainly used for research on eel farming and basic ecology and physiology of freshwater fish. >>Website (Japanese only).

Hamamatsu Association for Promotion of Specialized Eel Restaurants: Since its establishment in 1991, this organization has been carrying out various projects, including hosting events, in order to promote Hamamatsu as the “eel town.” >>English website.

Unagi Farmers and Producers in Western Shizuoka

Eel Farm Tenpo: Located on the shore of Lake Hamana, their main business is raising eels. But they also run a restaurant and an experience tour of their eel farm. >>Website (Japanese only).

Aikane Suisan: This is a long-established company with 90 years of tradition that specializes in eels. It wholesales eels from Lake Hamana to markets and eel specialty shops across the country. >>Website (Japanese only).

Ebisen: This is a seafood wholesaler in Hamamatsu, and deals in eel, shrimp, seafood, processed seafood products, and eel processed products. >>Website (Japanese only).

Vocational Schools in Western Shizuoka

Tokai Cooking and Confectionery Collage: This is a school where students learn Western cuisine, Japanese cuisine, Chinese cuisine, Western confectionery, and bread making through practical training. Petit Cazalis, the training restaurant attached to the school, offers restaurant internship and patisserie training, providing lunch, cakes and bread to the general public. >>Website (Japanese only)

OISCA Agri College: The current name of this school is OISCA Development Education College, but from April 2025 the name will be changed to OISCA Agri College. At this school, students learn the basics of agriculture through practical training. The training takes place in vast rice fields and tea plantations, and students learn about the cultivation of crops, quality control, vegetable harvesting, shipping, and sales processes. >>Website (Japanese only)

Hamamatsu Culinary and Confectionery College: At this school, students mainly study Japanese cuisine, Western cuisine, Chinese cuisine, and nursing care food. The school actively engages in interactions with local residents through corporate collaborations, event participation and planning, etc. >>Website (Japanese only)

Universities in Western Shizuoka

Hamamatsu Gakuin University (HGU): The Department of Regional Policy at this university develops students with advanced knowledge and skills in policy and management, while the Department of Tourism develops talent with specialized knowledge who can manage tourism in a way that is desirable for the local community, and the Department of Global Liberal Arts develops students with a global perspective and knowledge. >>Website (Japanese only)

Shizuoka University Of Art And Culture (SUAC): The Cultural Policy Department at this university offers a comprehensive study of the cultural perspective that is essential for urban development and corporate strategy in the 21st century. It aims to develop talented individuals who can contribute to the revitalization of local communities. >>English website

Western-style Restaurants in Western Shizuoka

El Camino: This is a Spanish dish restaurant located in Sanarudai, Hamamatsu. >>English website

Unagi-related Organizations in Central Shizuoka

The Shizuoka Eel Fisheries Cooperative: This organization was officially established by merging four eel farming associations in Shizuoka Prefecture. Now it offers eels that have been carefully raised by the 17 eel farmers, without any middlemen. >>Website (Japanese only).

Western-style Restaurants in Tokyo

gentil-H: This is a French dish restaurant located in Shirokanedai, Tokyo. >>Website (Japanese only)

Stores in Tokyo

Boranton PLUS: Located in Kunitachi, Tokyo, this shop deals with various eel-skin products. >>Website (Japanese only)

Nationwide Unagi-related Organizations

The National Grilled Eel Association: Formerly known as the National Federation of Grilled Eel Merchants Associations, this organization is made up of approximately 150 grilled eel shops throughout Japan. The headquarters is located in Nihonbashi, Tokyo. >>Website (Japanese only).

The All Japan Sustainable Eel Farming Organization: This nationwide body aims to ensure the sustainable use of eel resources, and engages in activities such as proper management of eels, promoting exchanges and cooperation among international eel farmers. >>Website (Japanese only).

Photo Credits, Sources, and Acknowledgements

Photographs by Koji Ikuma, unless otherwise noted. (Featured photo: “Basting unagi in the Kansai style at Hajime, Hamamatsu.”) Sources for this post include: 相曽保二『浜名湖うなぎ今昔物語』日本図書刊行会 (1998);静岡新聞社編『食考 浜名湖の恵み』静岡新聞社 (1997);静岡新聞社・南日本新聞社・宮崎日日新聞社編『ウナギNOW 絶滅の危機!! 伝統食は守れるのか?』静岡新聞社 (2016);塚本勝巳『うなぎ 一億年の謎を追う』学研教育出版 (2014). And we would like to thank: Professor William F. O’Connor for giving permission to quote a few sentences from his blog Drinking Japan; Hattori-Nakamura Suppon Farm for providing some precious photos for this post; Mr. Furuhashi from the Lake Hamana Fish Farming Cooperative for providing some useful information and advice; and President Yamashita at Tenpo for giving permission to use some photos from his eel farm. Also, we want to apologize in advance to those whose names are not mentioned here but should be.

Reference Links (New Window)

Outbound Links (New Window)