Overview of Hokuriku

Hokuriku refers to the area on the Japan-Sea side of the Chubu Region. It is sometimes called “The North Chubu Coast” in some English guidebooks. In terms of prefectures, it usually refers to the four prefectures of Niigata, Toyama, Ishikawa, and Fukui, but in some cases, it only refers to the three prefectures excluding Niigata. The cultural and commercial center of the Hokuriku region is Kanazawa, which is also one of Japan’s leading tourist cities.

Hokuriku is one of the areas in the world that receives the heaviest amount of snowfall in winter, with snow sometimes reaching 3 to 4 meters in the mountainous areas. There is little sunshine and heavy precipitation from autumn to winter, and it is even said that in Hokuriku it snows or rains one day out of two. Koshu Tani, a science fiction writer living in Komatsu City, Ishikawa Prefecture, once wrote the following about winter in Hokuriku: “Here, cold rain falls almost every day, with leaden clouds spreading across the sky, and it feels as if a heavy stone is being placed on my head.”

Another characteristic of the Hokuriku climate is the changeable weather. Here, blue skies often suddenly turn cloudy and a downpour occurs. Thunderstorms are also common. In Hokuriku, there is an old saying that goes, “Even if you forget your bento, don’t forget your umbrella.” (Bento is a Japanese-style lunch box.) They say that in Hokuriku, many people have had the experience of coming home from school soaking wet because they forgot to bring their umbrellas in the morning.

The area that is the southern half of present-day Ishikawa Prefecture was once the province known as Kaga, and its central city, Kanazawa, flourished as the “castle town of Kaga’s one million koku” with a population said to have exceeded 100,000 in the late Edo period. (Koku is a unit of rice yield that was used as an indicator of a domain’s economic power. A million koku was one of the largest among all domains in the country.) Furthermore, having escaped the damage of World War II, Kanazawa is a precious city where the historical scenery and castle townscape of the Edo period remain to this day.

Kanazawa has many attractive tourist spots, including Kenroku-en Garden, a nationally designated site of “special scenic beauty,” which is counted as one of Japan’s three most famous landscape gardens, along with Kairaku-en Garden in Mito and Koraku-en Garden in Okayama. In addition, Higashi Chaya District (also known as “the East Geisha Area”), near the Asano River, is home to a collection of traditional architecture called machiya (townhouses) with the narrow lattice windows, which continues to convey the high-class entertainment culture of the Edo period (1603-1868). Other places you should definitely visit include Kanazawa Castle, Omicho Market, and the Nagamachi samurai house district.

All the destinations I have listed above are of great tourist and historical value, and are worth taking the time to explore. The only drawback to these places is that they are always crowded with tourists, and sometimes you may feel as if you are in a historical theme park. In such cases, it might be a good idea to drive south in search of less familiar sites. With the flow of the Sai River behind you, drive south from Kanazawa and enter Hakusan City, and the mountains come closer. The castle town atmosphere will gradually fade, and instead there will be more places associated with Hakusan faith.

Mount Haku and Taicho

Hakusan, or Mount Haku (literally “White Mountain”), is one of the “Three Holly Mountains of Japan” along with Mt. Fuji and Mt. Tateyama. When people hear “Hakusan,” some may think of a single, independent peak, but in fact, “Hakusan” is a collective name for a group of 2,000-meter-class mountains, centered on Gozenga-mine (2,702m), Onanji-mine (2,684m), and Kenga-mine (2,677m). The area around this huge mountain range, stretching 40 kilometers north to south and 30 kilometers east to west, has been designated a national park since 1962.

In ancient Japanese Shintoism, which is based on animism, Mount Haku was revered as the god of water and agriculture, and was also believed to be a sacred mountain where the dead would enter. This is probably not surprising if you consider the fact that several large rivers, including the Tedori River, originate from Hakusan and flow through the plains, bringing the blessings of grain to ancient people. Then, when Buddhism was introduced from the continent in the 6th century, this new religion took root in Japanese society, not in conflict with Japan’s original forms of belief, but rather by fusing with them.

It was in this religious climate that Taicho appeared on the scene. He is said to have been the first person to climb Mount Haku and practice asceticism there in 717 (although it is still unclear whether he was a historical figure or a legend). It is often written that “Taicho opened up Hakusan in 717,” but in simple terms, “opened up” probably means that he, as a Shugendo monk, was the first to systematize the faith in Hakusan, incorporating elements of Buddhism and Taoism into the ancient Japanese primitive Shinto. After that, by the end of the 9th century, trailheads called banba (馬場, literally a “horse place”) were opened in each of the three provinces of Kaga (Ishikawa), Echizen (Fukui), and Mino (Gifu), and they became popular starting points for pilgrims climbing Mount Haku.

Shirayama Hime Shrine

The center of the banba on the Kaga side was Shirayama Hime Shrine in Tsurugi, Hakusan City. According to the shrine’s legend, this shrine was founded in 91 BC, which is almost an age of mythology. Then, in the Middle Ages, the shrine was bustling with devotees and Shugendo ascetics visiting Mount Haku, as it managed the summit of the mountain and collected the entry fees. Even today, with the vast grounds of over 40,000 square meters, it is the head shrine of over 2,000 Hakusan Shrines across Japan. (The “Hakusan Shrine” is basically a shrine that worships Mount Haku as its sacred object.) Okumiya (the inner shrine) of this shrine, located near the summit of Gozenga-mine, is said to have been founded by none other than Taicho himself.

In contrast to the masculine Tateyama mountain range in neighboring Toyama Prefecture, the graceful snow-capped Mount Haku evokes a serene and feminine image. It is not surprising, then, that the deity of Hakusan (and also the main deity of Hakusan Hime Shrine) is a goddess called Kukurihime no Mikoto (also known as Shirayamahime no Okami). She appears in the Nihon Shoki, one of Japan’s oldest historical books, as a deity who mediates the quarrel between Izanagi and Izanami, the male and female deities who created the Japanese land. That is why Kukurihime has long been worshiped as a deity of harmony and matchmaking. Even today many people visit Shirayama Hime Shrine to pray for goen (ご縁, “good encounters between people”).

Town of Tsurugi

If you still have time after visiting Hakusan Hime Shrine, it might be a good idea to take a stroll around the town of Tsurugi, which is close to the shrine. Tsurugi is a small district with a population of about 20,000, but it is a charming town with a long history and traditions. It was originally an administratively independent town called “Tsurugi-machi”, but since the establishment of Hakusan City in 2005 through the merger of municipalities, it has been the Tsurugi District of Hakusan City.

The name of Tsurugi was recorded in an ancient tourist book long before the name Kanazawa first appeared in historical documents. When you walk around the downtown area, you will see a couple of traditional wooden buildings, narrow and winding alleys, and irrigation channels flowing with clean water coming from the mountains. Although it is not a very famous tourist destination, the lack of tourists makes it a town that gives you a strange sense of nostalgia, as if you had traveled back in time to Japan of a generation ago.

The Tedori River, the largest river in Ishikawa Prefecture, originates in Mount Haku and flows north. In the middle reaches, it turns west, forming a large alluvial fan (the Kanazawa Plain) and flowing into the Sea of Japan. Tsurugi is a valley settlement located at the apex (the fan head) of this alluvial fan. For that reason, it has flourished as a market town where goods from the mountains were gathered since before the Middle Ages. In the Edo period, there are records that a lord of the Kaga domain (the Maeda clan) visited Hakusan along the Tsurugi Gaido that runs from Kanazawa.

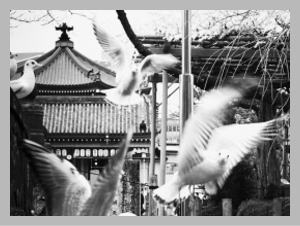

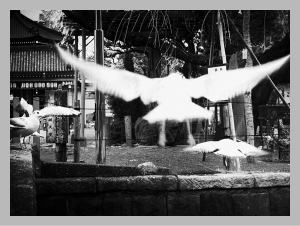

Today, Tsurugi is written in kanji characters as 鶴来 (meaning “Cranes are coming.”), but until the late-17the century, the character 剣 (sword) was applied for Tsurugi. This original fierce name was derived from Kinken-gu Shrine, the guardian deity of Tsurugi Town, as this shrine was formerly called Tsurugi no Miya (Shrine of the Sword). Kinken-gu was founded more than 2000 years ago and has been in this area since the founding of the Tsurugi settlement. In fact, the people of Tsurugi have a deep reverence for this shrine.

One autumn day, I visited Nishikawaya, a sushi restaurant just around the corner from Kinken-gu Shrine, for lunch, and the owner’s wife, a kind and friendly person, told me, “Hakusan Hime Shrine is famous throughout the country, but the residents of this particular area in Tsurugi have a deep reverence for Kinken-gu Shrine.” This shrine was also revered by successive military commanders and feudal lords as a god of martial arts and protection of life. It is known as a place where Minamoto no Yoshitsune once worshipped, and there is also historical evidence that Kiso Yoshinaka made an offering here.

Sake brewing and tobacco cultivation were thriving in Tsurugi Village during the Edo period. In particular, sake brewed in Tsurugi using water from Mount Haku was known as “Kikuzake of Kaga” and was the official sake of the Maeda clan of the Kaga domain. (Kikuzake literally means “chrysanthemum sake”, but there are various theories about the origin of the name.) Also, fitting with the original kanji character of Tsurugi, swordsmithing (cutting-tool forging) was thriving in this area, and in the Edo period, there was even a swordsmith who served as the official craftsman for the Kaga domain. After that, at least until the middle of the Showa period (1926-1989), a wide range of forged cutting-tools, such as hatchets, knives, and hoes, were made here, and they were shipped to the Kanto and Kansai regions.

The tradition of sake brewing is still carried on in the town of Tsurugi. In particular, the Manzairaku brewery has been brewing sake using melt water from Hakusan since its founding in 1716, and has won numerous awards in competitions both in Japan and abroad. On the other hand, it is very difficult to find a blacksmith who makes cutting-tools using traditional methods in Tsurugi these days. This is because the craftsmen are all aging and have no successors, and after the Second World War, low-priced, rust-resistant, mass-produced goods began to be circulated. I was certain that until ten years ago, there were still a couple of nokaji (野鍛冶, blacksmiths who specialize in making farm tools and kitchen knives) operating there, but when I spoke to the elderly proprietress of one of them, The Asano Hardware Store, in 2024, the answer I got was disappointing:

She said, “We stopped blacksmithing a few years ago. Now there is no one doing it in Tsurugi.”

“What happened to The Ota Blacksmith Factory?” I asked.

“Ota-san stopped before us, so did Nagai-san. Imawa daremo shitoran gaya desu (Now there is no one doing it.)”

Anyway, I continued my search a little further. Then I found a record that Ikeda Tokuhei Saw Factory, a blacksmith from Tsurugi, exhibited and sold traditional kitchen knives at the Ishikawa Prefectural Museum of Traditional Arts and Crafts in the spring of 2023. When I contacted the museum to confirm, the woman in charge politely explained to me: “Most of the blacksmiths in Tsurugi have stopped working, but this workshop is still open. This is the last one standing.”

“However, when I passed by the workshop, there was no sign of it being open, and when I called there, I couldn’t get through,” I said.

She replied, “I don’t know the details, but this blacksmith also does other work, so I think it’s difficult to respond.”

The video of him working in his studio was also uploaded to YouTube, which I have attached below.

❖ There is sound. Please be sure to wear your headphone.

The name Hakusan (White Mountain) comes from the fact that the peak remains covered with snow for most of the year, making it appear white from afar. However, it is quite difficult to see Hakusan from Kanazawa City. This is because, in the direction of Hakusan, there is a mountain called Mt. Kuragatake (565m), which hides the mountain. Therefore, if you want to see Hakusan, it is best to go a little further south from Kanazawa and view it from Kaga City or Komatsu City. Kyuya Fukada, author of “One Hundred Mountains of Japan,” said, “Hakusan is best viewed from my hometown on the Kaga Plain,” and wrote the following: “There are few clear days in the winter in Hokuriku. On the occasional clear night without a single cloud, Hakusan stands out in the blue moonlight like a work of crystal, like a scene from some unrealistic dreamland.”

Heisenji Hakusan Shrine

After driving south from the town of Tsurugi for about an hour along the mountain road, you enter Katsuyama City, Fukui Prefecture, and eventually come into view the forest on the old approach to Heisenji Hakusan Shrine. Present-day Fukui Prefecture was known as Echizen Province during the Edo period. While the above-mentioned Shirayama Hime Shrine was the base of Hakusan faith on the Kaga side, this Heisenji shrine was the base on the Echizen side. Heisenji is said to have been opened by Taicho 1,300 years ago. From behind the small San-no-Miya shrine, which is located at the very back of Heisenji’s precencts, a very long pilgrimage path called Echizen Zenjodo (越前禅定道) continues across several mountains to the top of Hakusan, and many religious ruins remain along the way even today.

When you arrive at Heisenji Hakusan Shrine, I recommend walking along the old approach, which stretches for about 700 meters, before entering the shrine’s precincts. This road is surrounded by dense rows of cedar trees that are hundreds of years old. This forest is called bodaibayashi, and bodai means “cutting off worldly desires and reaching the state of enlightenment.” It is said that the cobblestone pathway was built about 1,000 years ago by the monks of Heisenji, who carried the stones by hand from a nearby river while chanting sutras. This old road was designated one of the “100 Best Roads in Japan” in 1986.

Heisenji developed as a branch temple of Enryakuji Temple on Mount Hiei in the mid-12th century, and expanded its influence by forming successive alliances with the central powers of the time. It was at its most prosperous from the 14th to 15th centuries. At the time, it is said that dozens of buildings and thousands of living quarters for monks stood within its vast 200-hectare grounds, forming a magnificent religious city with an army of 8,000 warrior-monks. Historical warlords and influential people often donated land to Heisenji and requested military assistance.

However, in 1574, the entire temple grounds were burned down in a battle with the Echizen Ikko-ikki movement, and almost everything that tells of its former prosperity was lost. Ikko-ikki is the general term for armed uprisings that took place between the 15th and 16th centuries by followers of the Jodo Shinshu sect (Ikko sect) of Buddhism against established authorities. The rebels were mainly made up of peasants, merchants, and lower-ranking samurai, all united by the same faith, who sought to resolve their dissatisfaction with the politics of the time (such as heavy taxes) through organizational power.

The Ikko sect was particularly strong in the Hokuriku region at the time, and in the “Kaga Ikko-ikki” that occurred in the latter half of the 15th century, rebel forces drove out the governor (shugo) of Kaga Province and governed the province autonomously for about 100 years. (For this reason, Kaga at that time was called “The Peasants’ Kingom.”) In any case, after being destroyed by the Echizen Ikko-ikki in 1574, Heisenji managed to recover with the assistance of Toyotomi Hideyoshi and the subsequent Edo Shogunate, but to this day it has never regained the size and prosperity it boasted in the Middle Ages.

Apart from the fight against the Ikko-ikki, another major blow that Heisenji suffered in history was the Shinbutsu Bunri Order issued in 1868. (This was not limited to Heisenji, but was a path followed by most of Japan’s shrines and temples at that time.) Shinbutsu-bunri (神仏分離) refers to the separation of Shinto and Buddhism. The Meiji government at the time was planning to make Shinto the state religion, and ordered all shrines in the country to have Buddhist elements removed, which resulted in the demolition of many Buddhist buildings. This was also the trigger for the nationwide “Haibutsu kishaku movement,” in which a large amount of Buddhist implements and scriptures were discarded nationwide.

Before the issuance of this order, Heisenji was, strictly speaking, a Buddhist temple of the Tendai sect, but afterwards it became a Shinto shrine called Heisenji Hakusan Shrine. In other words, the previous state in which kami (Shinto deities) and hotoke (Buddhas) coexisted, which is called Shinbutsu-shugo (神仏習合), came to an end, and what Shinya Shirasu calls “a monotheistic religious dictatorship with Amaterasu Omikami at the top” began. After World War II, “freedom of religion” was granted in Japan under the new constitution, and the Shinbutsu Bunri Order is now long gone, but most Japanese shrines have yet to fully return to the way they were before this 1868 rule was enacted.

Today, under the lush cedar trees, the grounds of Heisenji are covered with beautiful moss that can be described as a “green carpet,” and pure air flows through them. It is said that there are a hundred different types of moss that can be seen here. Experts say that the high humidity is maintained on the grounds due to the heavy snowfall in winter, creating an ideal environment for moss to grow. Near the worship hall, there is a pile of what appears to be destroyed stone towers, but it is unclear whether these were destroyed as a result of the violence of the Ikko-ikki in the 16th century or during the anti-Buddhist movement in the 19th century.

Author Ryotaro Shiba is one of many people who were fascinated by the beauty of the moss at Heisenji, and in his book “Kaido Wo Yuku 18 – Echizen No Shodo (Walking Along Streets 18 – The Roads of Echizen),” he writes, “Compared to the scale and quality of the moss at Heisenji Hakusan Shrine, the moss at Kyoto’s “Moss Temple” is laughable.” In the same book, he also marvels at the fact that “in an age when tourism and profit-making at shrines and temples are the norm, admission is free here and there are almost no souvenir shops or the like.” Shiba published this book in 1982, but the current state of Heisenji seems not to have changed much since then, and this sort of “reluctant attitude toward tourism” seems to make the shrine’s presence even more pronounced.

According to legend, Taicho, the founder of Heisenji, was born in a place called Asouzu in Echizen (present-day Fukui City, Fukui Prefecture). As a teenager, he received a prophecy from the Eleven-faced Kannon in a dream, after which he retreated to his local mountain (Mount Ochi) and devoted himself to ascetic practice. In his mid-30s, a beautifully dressed goddess appeared in his dream and invited him to come to Hakusan. He accepted the invitation and set foot on Katsuyama in the year 717, and continued walking east until he reached a spring in the forest. This is the Mitarashi pond in the grounds of Heisenji today.

As Taicho stood by the spring and prayed, the goddess appeared again on the Yogoseki stone in the center of the pond and urged him to climb to the top of Hakusan. So he accompanied two ascetics and spent more than ten nights climbing the mountain to worship. After a thousand days of ascetic training at the peak, the three descended the mountain and built a shrine to worship the goddess of Hakusan on the side of the pond, where they lived and trained. This is said to be the beginning of Heisenji. Currently, on the east side of Mitarashi Pond, there stands an old cedar tree with a sacred shimenawa rope strung around it. This tree is said to have been planted by Taicho himself and is the sacred tree of Heisenji. The trunk splits into three parts midway through, which is said to symbolize the three shrines (three peaks) of Hakusan.

A short walk up the stone steps from the worship hall is the main shrine (Honsha), which enshrines Izanami-no-Mikoto, the deity of Hakusan’s Gozenga-mine peak. The original main shrine building was burned down in an attack by the Ikko-ikki rebels in 1574, but was rebuilt in 1795 with a donation from the lord of Fukui Domain. The exterior is made entirely of plain cypress wood. Splendid ascending and descending dragons support the eaves. With the main shrine in the center, Bessan-sha Shrine is located to the right and Onanji-sha Shrine to the left, representing the three peaks and their deities that make up Hakusan.

If you walk a little further south from the main shrine, you will come across a simple plain wooden torii gate. Passing through this gate, you will come to a small shrine called San-no-Miya. Located at the very back of Heisenji, it is dedicated to the god of safe childbirth. It is said that worshipping here will make your childbirth easier. Behind San-no-Miya runs a long pilgrimage path that leads to the peak of Mt. Hakusan, and this is the aforementioned Echizen Zenjodo. This is the path that Taicho is said to have actually used, and in 1996 it was selected as one of the “100 Best Historical Roads in Japan.”

The area south of this simple torii gate is called Minamidani (meaning “southern valley”), and is where excavation work is currently taking place. After Heisenji was burned down in the Ikko-ikki uprising in 1574, many of the buildings were buried under soil. (The grounds of Heisenji Temple at that time were said to be about 10 times its current size.) However, excavation work led by Katsuyama City, which began in 1989, revealed that the remains of the former temple grounds had been well preserved beneath the soil. The results of the ongoing excavation work are on display at the Mahoroba Museum, located near the Shojinzaka slope.

Getting There

In this post, I have introduced the route to Heisenji Hakusan Shrine by car from Kanazawa via the town of Tsurugi. However, if your only destination is Heisenji, the most convenient way would be to take the train to JR Fukui Station and then use a car (rental car or taxi, etc.) from there. In that case, if the roads are not congested, you can reach Heisenji in about 50 minutes using the Chubu Jukan Expressway.

Other Photos

Places Nearby

Relatively close to Heisenji Hakusan Shrine are at least two of the most popular spots in Fukui Prefecture: the Fukui Prefectural Dinosaur Museum and Eiheiji Temple. Hokuriku is home to 120 million-year-old dinosaur-era strata, and Fukui Prefecture boasts the largest number of dinosaur fossils excavated in Japan. This Dinosaur Museum displays over 40 dinosaur skeletons, making it a place that both adults and children can enjoy. Eiheiji Temple is the head temple of the Soto sect of Buddhism, founded by Dogen in the 13th century, and many monks still train here today. It is also fun to stroll around the temple town lined with about 40 shops.

If you don’t mind not going to popular tourist spots, it might be a good idea to visit the places associated with Taicho scattered around Fukui Prefecture. As mentioned above, it is unclear whether Taicho was a fictional character or a real person, but there are many anecdotes about him, mainly in Fukui Prefecture. Ryotaro Shiba was one of those who supported the theory that Taicho actually existed, and he writes that the reason Taicho’s name does not appear in national histories from the Nara period (710-794) is probably because he was not an official monk but a private ascetic with some knowledge of Buddhism. Also, the writer Masako Shirasu followed in Taicho’s footsteps during her lifetime, visiting Taicho-ji Temple, which stands in the place where Taicho is said to have been born, and Otan-ji Temple in Echizen Town, where Taicho is said to have spent his later years.

Ochi-san (Mount Ochi), where Taicho is said to have practiced asceticism in his teens, is about six kilometers west of Otan-ji Temple in a straight line and only about five kilometers from the Sea of Japan. There is an observation deck near the peak of the mountain, which is about 612 meters above sea level, and from this mountain, Hakusan and Heisenji are located almost due east. In her book “Kakurezato” (literally, “Hidden Villages”), Masako Shirasu writes, “From here, the young Taicho must have worshipped the sunrise over Mount Haku at dawn, and in the evening, he gazed upon the Sea of Japan tinted with the setting sun. It may have been at such a moment that the Eleven-faced Kannon appeared to him, and, longing for its image, he decided to climb Hakusan.”

❖ There is sound. Please be sure to wear your headphone.

Last Statement & Contact

In March 2024, the Hokuriku Shinkansen was extended to JR Tsuruga Station in Fukui Prefecture, making it even more convenient to travel from central Tokyo to Hokuriku. At the same time, tourist spots scattered throughout Hokuriku are attracting renewed attention. You can travel around the tourist spots in Kanazawa City by bus or taxi, or rent a car to see the various parts of Hokuriku. However, the mountainous areas of Hokuriku are subject to heavy snowfall, so please be careful when visiting by car in winter. Also, black bears have been spotted from time to time around Shirayama Hime Shrine and Heisenji Hakusan Shrine. So, if you visit these shrines alone, especially in the dark hours of the late autumn evening before their hibernation, you may want to be careful of bear attacks. If you are interested in a tour to visit a couple of spots in Hokuriku, please send a message through the Rate/Contact page of this website.

Photo Credits, Sources, and Acknowledgements

Photographs by Koji Ikuma, unless otherwise noted. (Featured photo: “Entrance to Kinken-gu Shrine in Tsurugi.”) Sources for this post include: 『角川日本地名大辞典17石川県』角川書店(1981);『ふるさとの文化遺産 郷土資料事典17: 石川県』人文社(1997);『日本の名山18: 白山』博品社(1998); 白洲正子『かくれ里』講談社(1991); 司馬遼太郎『<ワイド版>街道をゆく18: 越前の諸道』朝日新聞出版(2005); 井沢元彦『逆説の日本史(8)中世混沌編』小学館(2004); 高樹のぶ子『透光の樹』文藝春秋(1999); 白洲信哉『白洲正子の宿題:「日本の神」とは何か』世界文化社(2007); 深田久弥『日本百名山』新潮社(1978)And we would like to thank: the Nomi Furusato Museum for giving permission to use one of their images.

Outbound Links (New Window)