Last update: August 2025

Tokyo (in the Kanto region) is the capital of Japan and also the most populous region in the country. The so-called “Special Ward area,” an area consisting of 23 municipal wards and forming the core of the city, alone has, as of 2025, a population of approximately 9.8 million people, which is more than the population of the entire Kanagawa Prefecture. In particular, the area centered on the Imperial Palace in Chiyoda Ward is Japan’s political center, where the Diet (national parliament building), the Supreme Court, the Prime Minister’s residence, and the headquarters buildings of each ministry are located. And at the same time, it is the economic center with the country’s largest business districts such as Otemachi, Marunouchi, and Yurakucho. (These three areas are sometimes collectively referred to as the “OMY district.”)

Tokyo Station

Tokyo Station is located on the eastern edge of Chiyoda Ward. It is one of the busiest stations in Japan, with more than 4,000 trains arriving and departing every day. And it is said that more than one million people use the station daily. Tokyo Station is not just a train station, but a huge complex building that also houses a hotel and a gallery, and both inside and outside the ticket gates are filled with restaurants, bars, and souvenir shops in a maze-like pattern, making the area more like a city bustling with people than a station.

When you go out of Tokyo Station and want to explore, roughly speaking, you can either exit from the Yaesu side to the east side or exit from the Marunouchi side to the west side. The Yaesu and Marunouchi sides are connected by the central passageways, so you can freely move between the two sides without buying a ticket and going through the ticket gates. The Yaesu side has the Daimaru department store building in the center, and the Yaesu Underground Mall, one of the largest underground malls in Japan, spreads out underground. In addition, the huge building of Tokyo Midtown Yaesu opened in 2023. This area has been rapidly developing commercially in recent years. The Yaesu side is closest to the Shinkansen platforms, so people coming from other parts of Japan by Shinkansen might be more familiar with the Yaesu side than the Marunouchi side.

However, the highlight of Tokyo Station is undoubtedly the Marunouchi side, where the red-brick station facade exudes a retro atmosphere. This Tokyo Station Marunouchi Building is packed with Japan’s history from modern times to the present. When Tokyo Station first opened in 1914, there was no station building on the Yaesu side, and people coming from Nihonbashi or Kyobashi had no choice but to go around to the Marunouchi side by going under the elevated tracks. It was not until 1929, 15 years after the station’s opening, that a small station building was built on the Yaesu side.

It is well known that the Tokyo Station Marunouchi Building was designed by Tatsuno Kingo, known as the “father of modern Japanese architecture,” but not many people know that the original designer was Franz Baltzer, a German. (Incidentally, Tokyo Station was just called Chuo Teishajo, or the “Central Station,” during the design stage.) Baltzer’s idea was to line up small brick buildings on the side of the tracks, with Japanese-style roof tiles on each roof. Baltzer himself seemed to think, “As it is a station that represents Japan, it is appropriate to use a uniquely Japanese architectural style.” But his design idea was rejected as being “too shabby for the central station of the imperial capital,” and Tatsuno Kingo was eventually asked to take over, with the request for “something more spectacular.”

It was December 1910 when Tatsuno completed all the design work for the building. It was nearly eight years since he had taken over from Baltzer in 1903. According to Tatsuno’s recollections, initially, a sufficient construction budget was not approved, so the design had to lack grandeur. However, after Japan won the war against Russia in 1905, there was a growing momentum to “build a station worthy of being the front door to Japan, which had won against the great power Russia,” and the construction budget was significantly increased, making it possible to design on a larger scale.

On December 14, 1914, a magnificent three-story station building with dome-shaped roofs on both sides was completed. The structure was made of steel-framed bricks, making it extremely sturdy. Tatsuno wrote that because Japan is prone to earthquakes, bricks and stones alone were not enough to provide security, so iron materials were added. There used to be a popular myth that Tokyo Station was modeled after Amsterdam Central Station, and many people believed it. However, quite a few experts deny this today. They say, technically, the two station buildings have different architectural styles. (However, it is true that the appearances of these two stations are similar, and in fact, the two stations became sister stations in 2006.)

Four days later, on December 18, the opening ceremony for Tokyo Station was held under a clear blue sky. The Prime Minister at the time, Okuma Shigenobu, took to the podium and said, “The power of railways is great, and the communication of ideas and military operations are greatly dependent on them.” After the ceremony was closed, the guests were led to the platform, where a train carrying General Kamio and his staff quietly glided in while a military band played music. In World War I, which broke out that year, Kamio, commander of the 18th Division, had distinguished himself in the seizure of Tsingtao from the German fleet. Kamio’s triumphant return to the imperial capital and the opening ceremony for Tokyo Station were purposely scheduled to take place on the same day.

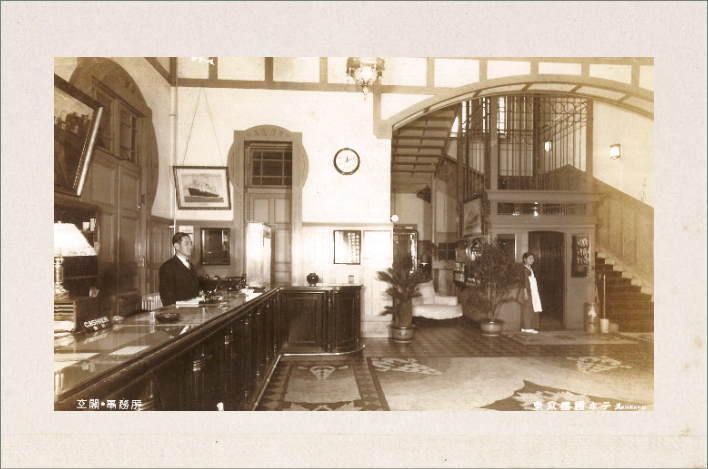

One year after its opening, the Tokyo Station Hotel opened inside the building, and Tokyo Station continued to develop smoothly. Even when the Great Kanto Earthquake occurred in 1923, the building remained almost unscathed thanks to Tatsuno Kingo’s careful earthquake-resistant design. The most serious damage that the Marunouchi structure suffered in its history was during an air raid from midnight on May 25th to 26th, 1945, during World War II. Countless incendiary bombs ignited the building, turning it into a hearth-like state, with the dome roofs and the entire third floor burning away. Restoration work was carried out at a rapid pace, and in March 1947 the building was rebuilt with two main floors and a small part of the third floor. At this time, the dome roofs were replaced with pyramid-like octagonal roofs, and the elaborate design of the interior ceiling was simplified.

Although there were plans to demolish the aging station building and replace it with a modern high-rise building, public opinion in favor of preserving the original building gradually started to grow around the late 1980s. And, in 1999, under then Tokyo Governor Shintaro Ishihara, the decision was made to officially preserve and restore the Tokyo Station Marunouchi Building. Then, in 2003, the building was designated an Important Cultural Property by the government as a “valuable piece of architecture that symbolizes the capital, Tokyo.” Finally, in 2007, construction began using the original blueprints and pre-war photographs as clues, and in October 2012, the Tokyo Station Marunouchi Building was restored to its original three-story, domed appearance.

Overview of the Imperial Palace

If you leave Tokyo Station from the Marunouchi side and walk west along Gyoko-dori Avenue for about 500 meters, you will come to Uchibori-dori Avenue. On the right side is Wadakura Fountain Park, a beautiful park with artistic fountains and seasonal flowers, originally built in 1961 to commemorate the marriage of Emperor Emeritus Akihito, the abdicated former Emperor, and on the left is a spacious area of lawn and black pine trees. This area is the southeastern corner of the Imperial Palace, known as the Imperial Palace Outer Gardens (Kokyo Gaien). There is also a parking lot for tourist buses in the Outer Gardens, where you will find a bronze statue of Kusunoki Masashige, a 14th century military commander who fought in loyalty to Emperor Godaigo at the time.

A few minutes’ walk from the statue brings you to the most well-known area of the Imperial Palace, which is the area in front of the Main Gate (to the Palace). There you will find a photogenic double-arched stone bridge spanning the moat. This bridge is often mistakenly called Nijubashi (literally “double bridge”), but its official name is Seimon Ishibashi (Main Gate Stone Bridge), and it is also colloquially known as “Meganebashi” (Spectacles Bridge) due to its shape. Behind this stone bridge is an iron bridge called Seimon Tetsubashi (Main Gate Iron Bridge) spanning the moat, which is in fact the real Nijubashi bridge. The name comes from the fact that the original wooden bridge, before it was replaced with an iron bridge in 1888, had a double-girder structure. Also, just a short walk from here is the Sakurada-mon Gate, famous for the Sakurada-mon Incident of 1860.

Once you cross this iron bridge, you enter the Palace District, where the Imperial Household Agency’s building and the palace for welcoming domestic and international dignitaries are located. This is the area where more than 20 traditional ceremonies take place each year. (Incidentally, the current Emperor of Japan and his family live in a residence in the Fukiage Gardens, which occupies the northern part of the Palace District.) However, the Imperial Palace’s Gijotai guards takes turns guarding the main gate, and ordinary people are not usually allowed to enter the Palace District except on special occasions. Those “special occasions” include the New Year’s General Audience on January 2nd, when the Emperor and Empress and other members of the Imperial Family appear on the balcony of Chowaden Hall and wave to the public, and the Emperor’s birthday. For more information on how to visit some sections of the Palace District, please see the Imperial Household Agency website. (The YouTube clip below shows Emperor Naruhito and Princess Aiko watching a performance of gagaku, which is an ancient Japanese court music, at the Imperial Palace.)

❖ There is sound. Please be sure to wear your headphone.

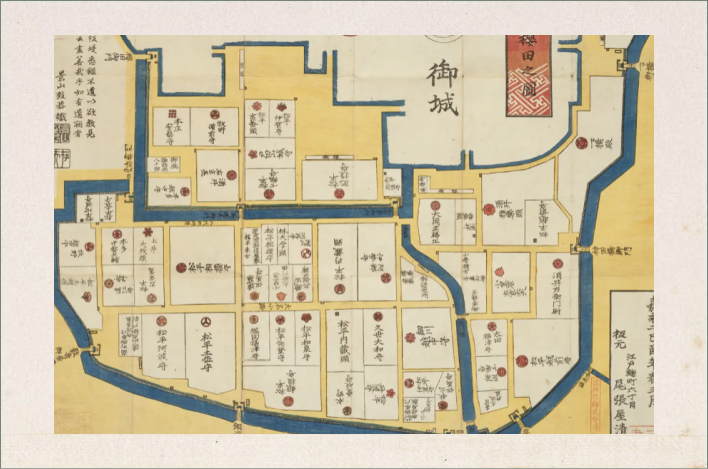

The land where the current Imperial Palace is located was originally the site of a huge castle called Edo Castle. A military commander named Ota Dokan built the original castle here in 1457, and in 1590 it became the residence of Tokugawa Ieyasu. When Ieyasu established the Edo Shogunate in 1603, Edo Castle became the center of politics and administration, and full-scale urban development was carried out. The central parts of Edo Castle at that time, including the Honmaru (main enclosure) and Ninomaru (second enclosure), were located in the area that is now the Imperial Palace East Gardens (Higashi Gyoen). It is said that the largest castle tower (tenshu) in Japan, standing 58 meters above ground, once stood in the Honmaru, but it was destroyed in the great fire of 1657, and has not been rebuilt since. Today, only the massive stone base remains in the East Gardens.

During the Edo period, when successive Tokugawa shoguns held real political power in Japan, the residence of the Japanese imperial family was in Kyoto. After the Edo Shogunate fell in 1867, Edo was renamed Tokyo (meaning “Eastern Capital”) by the new Meiji government, and in 1869 Emperor Meiji moved from Kyoto to the current Imperial Palace.

Overview of Marunouchi

Now, with that preamble out of the way, I’d like to talk about Marunouchi, which is the main subject of this post. Marunouchi is an area of approximately 65 hectares located between the Imperial Palace Outer Garden and Tokyo Station. With over 100 modern buildings, it is one of Japan’s leading office districts. However, at the same time, Marunouchi is also home to fashionable shopping streets with a European atmosphere, such as Marunouchi Naka-dori Street, and the Marunouchi Brick Square, which has a courtyard filled with greenery and a fountain, making it a town that has both business and tourist aspects. The Marunouchi Building and Shin-Marunouchi Building also have many carefully selected restaurants and shops. In addition, there are many opportunities to experience high-quality art, including art galleries, museums, and public art. However, Marunouchi’s multifaceted appeal was not achieved overnight.

The land where Marunouchi is currently located was once a sea about two meters deep called Hibiya Cove. In the late 16th century, large-scale land reclamation work was carried out to expand Edo Castle, creating the land of today’s Marunouchi. During the Edo period, due to its proximity to the Honmaru of Edo Castle, magnificent samurai residences lined the area, and it was called Daimyo-koji (the Daimyo Alley). Following the Meiji Restoration, many of the feudal lords returned to their home provinces, and the vast feudal lord residences were used as government offices and residences for high-ranking officials of the new Meiji government, as well as army barracks.

These barracks were gradually relocated to neighboring areas such as Akasaka and Azabu, and in 1889 the Meiji government officially decided to sell the land of Marunouchi to the private sector. The following year, Marunouchi was purchased by Iwasaki Yanosuke, president of Mitsubishi. The first thing Iwasaki did was demolish the buildings on the land he had purchased. So, for a while, the Marunouchi land resembled a vast field, earning it the nickname “Mitsubishi-ga-Hara” (Mitsubishi Fields). However, even back then Iwasaki had a clear plan in mind for building a Western-style urban area on this site, with the intention of demonstrating, to both domestic and international people, Bunmei-kaika (“civilization and enlightenment”) that had resulted from the Meiji Restoration. And systematic development would take place over the next 70 years.

To begin with, construction of the Mitsubishi Ichigokan, Japan’s first office building, began in 1892 and was completed in 1894. Designed by British architect Josiah Conder, known for his work on the Rokumeikan, it was a beautiful, British-style, three-story red brick building, and housed a bank and other businesses. Following it, buildings of the same type were constructed one after another. The sight of rows of red brick buildings looked just like the streets of London, and Marunouchi at the time was nicknamed the “London Block.” (Incidentally, the Mitsubishi Ichigokan Building was demolished in 1968 but was later faithfully restored to its original form and opened as the Mitsubishi Ichigokan Museum in a corner of Marunouchi Brick Square in 2010. Since then, it has become one of Marunouchi’s most popular spots as a building that tells the story of Marunouchi’s history.)

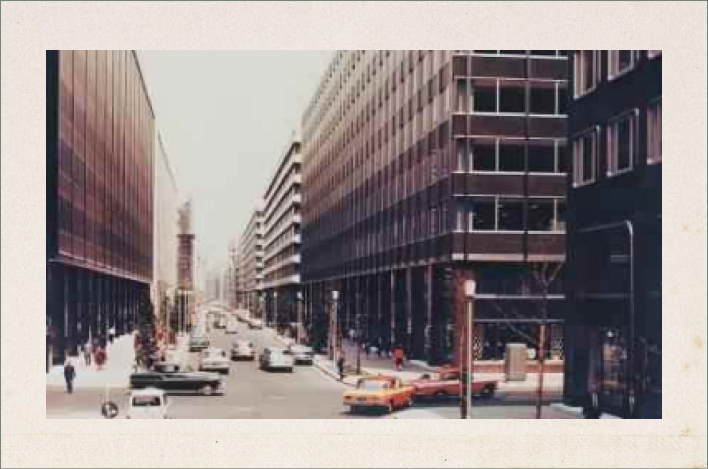

Tokyo Station opened in 1914, dramatically improving access to the center of Marunouchi. Then, in February 1923, the eight-story Marunouchi Building (the original building) was completed in front of the station. The lower floors housed shopping malls, unusual for the time. After World War II, Marunouchi rode the wave of rapid economic growth, and by around 1970, large buildings were constructed one after another. At the same time, Marunouchi’s working population rapidly increased. In the 1990s, office buildings began to be constructed in emerging areas such as Ebisu, Shinagawa, and Shiodome, and businesses and people gradually shifted their attention to these areas. By that time, Marunouchi had been perceived as an “old office district.” During the day, only office workers wearing a suit would walk down Marunouchi Naka-dori Street. On weekday evenings and weekends, the area was virtually deserted.

It was in the late 1990s that full-scale efforts to put an end to this “stagnation period” and transform Marunouchi into a vibrant neighborhood began. A symbolic milestone was the launch of the “Advisory Committee on Otemachi-Marunouchi-Yurakucho Area Development” (hereinafter referred to as the “Committee”) in 1996. This groundbreaking, public-private collaboration brought together the “Council for Area Development and Management of Otemachi, Marunouchi, and Yurakucho Area” (hereinafter referred to as the “Council,” which was comprised of local landowners in Marunouchi), the Tokyo Metropolitan Government, Chiyoda Ward, and JR East, to exchange ideas. One of the ideas behind this Committee was “urban development that emphasizes the intangible aspects.” While traditional urban development in Japan has focused on the tangible elements, such as facilities and infrastructure, the idea was that a focus on “nurturing the city” and “enjoying the city” was essential to sustaining public interest after development.

The two pillars of the Marunouchi regeneration project that the Committee set out were the reconstruction of the Marunouchi Building and the redevelopment of Marunouchi Naka-dori Street. In 2002, the Marunouchi Building was reborn as a 180-meter-tall, 37-story building, which houses many restaurants, shops, and offices. To this day, it stands as a landmark of Marunouchi, alongside the neighboring Shin-Marunouchi Building. The exterior of the lower floors has been recreated to look just as it did when the building was first built, but what is noteworthy is that the Naka-dori side (west side) of these lower floors has an open atrium. This was designed with the aim of hosting a variety of events here and turning Marunouchi into a district that disseminates cultural information.

Marunouchi Naka-dori Street

Naka-dori Street is a fashionable street that runs north-south through the heart of Japan’s economy, encompassing not only the Marunouchi area but also Otemachi to the north and Yurakucho to the south. While the street has been central to the Marunouchi area since the London Block days, until the 1990s it was essentially a quiet business district, not a place for fashionable dining and shopping. Meanwhile, its Yurakucho section already boasted several commercial facilities, including luxury brand stores. The problem was that almost no one crossed Babasaki-dori Avenue from there to the Marunouchi side for leisure. The Committee members’ main goal was to enhance the appeal of Marunouchi Naka-dori Street, which connects the Yurakucho area with the Tokyo Station district, home to the Marunouchi Building and Shin-Marunouchi Building, and to increase the overall accessibility and vitality of the area.

Today, Marunouchi Naka-dori Street is a charming cobblestone street lined with brand shops, roadside trees, artworks, and open-air cafes. Benches are available everywhere for a rest. The street is bustling with shoppers on weekdays and holidays. Even at night, couples and tourists can be found enjoying meals. It is difficult to imagine the bustling street it is today from a photograph of Naka-dori taken more than 25 years ago, showing its bleak appearance. Behind this transformation lies persistent coordination with the police and local government, as well as the hard work of many staff and landowners.

For example, Naka-dori Street previously featured a wide, one-way roadway with cars parked on both sides of the road, but the roadway width was narrowed and the sidewalks widened in line with a pedestrian-first road design. Furthermore, to minimize the presence of cars on Naka-dori Street, the Naka-dori side was basically designed without access to parking. The expanded sidewalk space allowed for the placement of small benches and planters, creating numerous small spaces for pedestrians to relax. The cobblestones on both the sidewalk and roadway are made of Argentine porphyry, a material commonly used for pavements in Europe. All of these improvements were based on the concept of “shifting from a car-centric street to a people-centric street.” Currently, vehicle traffic is restricted on portions of Naka-dori Street from 11:00 to 15:00 on weekdays and from 11:00 to 17:00 on Saturdays, Sundays, and holidays. During these times, the roadway is open to pedestrians, allowing for a variety of activities.

In order to realize “people-centered urban development,” the selection of street trees was also an important element. Previously, Naka-dori Street was lined with tulip trees, but now the streetscape is created by combining several different types of trees. Each of these trees loses its leaves at a different time, allowing people to enjoy the autumn colors at different times. Of these, the main tree is the zelkova, whose branches and leaves spread out in a fan shape, creating a green tunnel that not only creates a beautiful streetscape but also provides pleasant shade in the summer.

These new initiatives aimed at revitalizing Naka-dori Street were primarily planned in accordance with the “Urban Development Guidelines” approved by the Committee. Based on these Guidelines, the OMY Area Management Association (commonly known as “Ligare”) was established in 2002 as a new organization responsible for “intangible urban development.” Since then, Ligare has promoted a wide range of projects, and has successfully hosted numerous events, including the OMY Summer Festival. In addition to the Council and Ligare, the “Association for Creating Sustainability in Urban Development of the OMY District” (commonly known as the “Ecozzeria Association”) was established in 2007 with the aim of addressing various social issues. Currently, these three organizations, each with their own distinct roles, are working to further transform the area for the future.

In addition to the large-scale events organized by Ligare, smaller events—such as small-group photo sessions—can occasionally be found on Marunouchi Naka-dori Street. I myself participated in one such event one day in June, before the COVID-19 pandemic. It was a workshop on “Natural Light Portraiture” hosted by FUJIFILM Corporation. The instructor was renowned portrait photographer Ichiro Fujisato (@shameraman), and Rino (@mana143x5) served as the model. (Some of the photos of Naka-dori Street used on this page were taken during the workshop.) First, Mr. Fujisato demonstrated how to take a portrait to the participants, and as he spoke to Rino while taking the photos, you could see her expression gradually relax. It was truly a professional job. After the demonstration, each participant was given time to take photos.

Getting There

Marunouchi Naka-dori Street is just a few minutes’ walk from both the Marunouchi exit of Tokyo Station and the Imperial Palace Outer Gardens.

Other Attractions

There are so many places worth seeing within the vast grounds of the Imperial Palace and its surrounding area that it would be impossible to introduce them all on this page, but I would like to introduce a few more below. The Imperial Palace East Gardens, which I mentioned briefly above, can be entered through three gates. Of these, the Otemon Gate on the east side was the main gate of the former Edo Castle, and today the majority of visitors to the East Gardens use this gate. However, it is also interesting to occasionally enter through the Hirakawa-mon Gate on the north side, where you can see a different view. This gate is a little far to walk from Tokyo Station, and the nearest station is Takebashi Station on the Tokyo Metro Tozai Line.

During the Edo period, Hirakawa-mon Gate was primarily used by women working in the Shogun’s palace. Like the Otemon Gate, it is a heavily fortified structure consisting of two gates: the Koraimon Gate (the entrance gate) and the sturdy Watariyagura-mon Gate. Adjacent to Watariyagura-mon is a small gate called Obikuruwa-mon Gate, also known as the “Gate of Impurity.” It is said that criminals, dead bodies, and feces from within the castle would be carried out from this small gate. The bridge spanning the moat in front of Hirakawa-mon Gate, called the Hirakawa-bashi Bridge, still retains the appearance of a wooden bridge from the Edo period. While the bridge itself was renovated during the Showa era, some of the bronze giboshi (decorative ornaments used on the railings) date back to the early 17th century.

Passing through the Hirakawa-mon Gate and walking along the road, you will come to a stone-walled slope on your right. This is the Shiomi-zaka, literally meaning the “Tide-view Slope.” Long ago, Hibiya Cove extended close to the present-day Imperial Palace Plaza, affording a commanding view of the sea from this slope, hence the name. At the top of the slope is the former Edo Castle Honmaru, where the castle tower once stood. To the east of the Shiomi-zaka lies a grove of trees. This is the Ninomaru Grove, which was developed over three years at the initiative of Emperor Showa (1901-1989). Passing through this grove, you will find the Ninomaru Japanese Garden, located on the eastern edge. This strolling garden with a pond was restored based on drawings from the time of the ninth Tokugawa Shogun, Ieshige (1712-1761). It is a place where you can enjoy a variety of flowers throughout the year, including irises in June.

Admission to the Imperial Palace East Gardens is free and open to the public, but please note that it is usually closed on Mondays and Fridays (as of August 2025). Guided tours are also available with advance reservations. For more information, please visit the Imperial Household Agency’s website.

In addition to the Mitsubishi Ichigokan Museum mentioned above, another historic attraction in Marunouchi is the Meiji Seimei Kan building. This large, stately stone structure was designed by architect Okada Shinichiro at the request of Meiji Insurance Company at the time and completed in 1934. Although it escaped damage during the air raids at the end of World War II, it was requisitioned by the General Headquarters (GHQ) under the Supreme Commander Douglas MacArthur after the war and used as the headquarters of the American Far East Air Force (FEAF).

The second-floor conference room regularly hosted the “Allied Council for Japan” (ACJ), a meeting of representatives from the United States, Britain, China, and the Soviet Union, and MacArthur himself attended many of these meetings. Thus, Meiji Seimei Kan has survived the turbulent days of the Showa era (1926-1989). It remains highly regarded today as a masterpiece of classical style, and in 1997, it became the first Showa-era building to be designated an Important Cultural Property by the Japanese government. Currently, part of its interior is open to the public free of charge, and after checking in on the second floor, you can tour the conference room, reception room, dining room, etc.

The above photo shows the exterior of the Meiji Seimei Kan building, taken from the Imperial Palace Outer Gardens. From this vantage point, the building’s majestic architectural style, with its rows of Corinthian columns, is clearly visible. The high-rise building behind Meiji Seimei Kan is the Meiji Yasuda Life Insurance Company headquarters building, completed in 2004, and its facade faces Marunouchi Naka-dori Street. The lower floors of this building form a spacious atrium, which is internally connected to Meiji Seimei Kan. The same building is home to the Seikado Bunko Art Museum, which was relocated from Setagaya Ward in 2022. It displays a collection of Oriental art collected by Mitsubishi’s second president, Iwasaki Yanosuke, and his son, Koyata.

❖ There is sound. Please be sure to wear your headphone.

Other Photos

Conclusion & Contact

The area west of Tokyo Station, introduced in this post, is one of the most fascinating areas in Tokyo, brimming with Japanese history from the modern era to the present. Even though it’s nestled between skyscrapers, it’s also rich in seasonal flowers and greenery. If you’re interested in a walking tour focusing on Tokyo Station, Marunouchi, and the Imperial Palace, please send a message through the Rate/Contact page of this website.

Photo Credits, Sources, and Acknowledgements

Photographs by Koji Ikuma, unless otherwise noted. (Featured photo: “Portrait workshop at Marunouchi Naka-dori Street.”) Sources for this post include: 岡本かの子『丸ノ内草話』青年書房(1939); 伊藤かんじゅん『パノラマ写真で皇居一周』TOKIMEKIパブリッシング(2010);『図解 天皇126代』宝島社(2024); 辻聡『東京駅の履歴書』交通新聞社(2012); 岡本哲志『「丸ノ内」の歴史』武田ランダムハウスジャパン(2009); 大丸有エリアマネジメント協会 丸の内仲通り本編集室『丸ノ内仲通り』幻冬舎(2019); 岡本哲志『一丁倫敦と丸ノ内スタイル』求龍堂(2009); 藤里一郎『ポートレイトノススメ』日本写真企画(2016); 竹内正浩『皇居の歩き方』小学館(2019)And we would like to thank Mitsubishi Estate and Fujifilm Imaging Plaza for giving permission to use some of the images.

Outbound Links (New Window)