◆ This post is still a Work In Progress. ◆

Introduction

Hakone (pronounced “ha-ko-ne”) is a scenic spot and one of Japan’s most famous tourist destinations. As such, it is always bustling with tourists from both within and outside of Japan. Geographically, Hakone refers to the area around the Hakone Caldera in the southwestern corner of Kanagawa Prefecture, near Shizuoka Prefecture, and is part of the Fuji-Hakone-Izu National Park. However, Hakone is an area with many facets of appeal, including hot springs, history, nature, and art, making it difficult to describe in a single word. Geographical Hakone is probably larger than you might imagine and is made up of several fascinating area

When people think of Hakone, they probably think of the postcard-perfect scenery of Lake Ashi with Mount Fuji in the background, the desolate landscape of Owakudani with its sulfurous smell, or the hot springs gushing out everywhere (the total amount of hot spring water gushing out from Hakone is nearly 20,000 liters per minute). Some may even have ridden the Hakone Tozan Railway or Hakone Ropeway. And if you’re into art, Hakone is dotted with numerous art galleries and museums.

Some people may also associate Hakone with the Hakone Ekiden (an inter-university relay marathon held every New Year) or Hakone Yosegi-zaiku (a traditional Hakone craft that dates back to the Edo period and is one of the most popular souvenirs). In this post, I will begin by briefly outlining the more commonly known aspects of Hakone, and then in the second half, I would like to introduce some lesser known destinations and lesser known aspects of Hakone.

Overview of Hakone

The Hakone region, with its chain of 1,000-meter-high mountains, generally exhibits a mountainous climate. It is characterized by heavy rainfall, high humidity, and rapid weather changes. During the rainy season in June and July, strong southwesterly winds and frequent fog occur. Summers are cool, but there is considerable rainfall even in September. High-altitude areas often experience snowfall in winter. Hakone’s frequent fog is said to be due to its topography, where moist air from the warm Pacific Ocean collides with the mountains. Due to this climate, there is a rich variety of plant life. As for animals, wild boars, hares, and weasels can be seen in Hakone. Japanese macaques have also been spotted in some areas.

The classic 1900s Japanese song “Hakone Hachiri,” with lyrics by Torii Makoto and music by Taki Rentaro, begins with the lyrics, “Hakone no yama wa tenka no ken,” which means “The mountains of Hakone are world-famous, rugged mountains.” Even today, the television coverage of the annual Hakone Ekiden race offers a glimpse into the ruggedness of Hakone’s mountain trails. These rugged mountains were once a sacred place for mountain worship. Hakone has also long been known as an area where hot springs gush forth. The first hot spring in Hakone was discovered in 738 during the Nara period, when Shaku Jojobo discovered it in Hakone Yumoto.

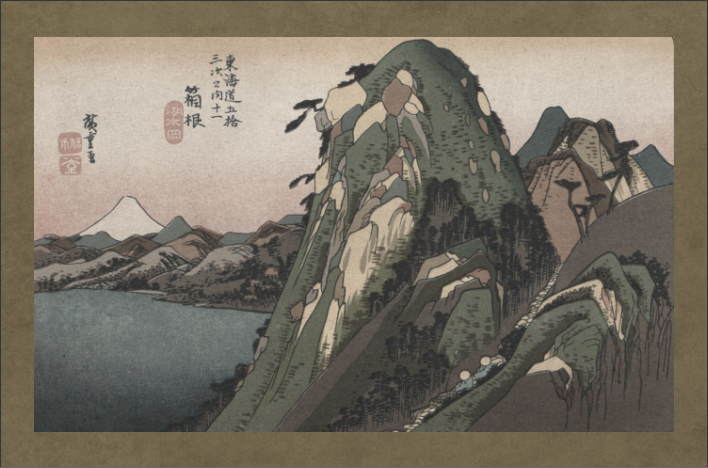

As time passed and the Edo period began, Hakone was designated the 10th post station town (shukuba) on the Tokaido Highway, counting from Edo, and the surrounding villages rapidly prospered. However, as the lyrics of the song quoted above suggest, the steep mountain roads of Hakone posed a significant challenge for travelers along the Tokaido. Even today, Hakone retains many cultural and historical sites that convey its history, such as the cobblestones of the Old Hakone Highway. Also, during the Edo period, Hakone’s hot springs became extremely popular among people, and Hakone developed greatly as a hot spring resort. At the time, Hakone’s seven famous hot springs – Hakone Yumoto, Tonosawa, Miyanoshita, Dogashima, Sokokura, Kiga, and Ashinoyu – were known as Hakone Nanayu (or the “Seven Hot Springs of Hakone”) and attracted many travelers.

As the Edo period ended and the Meiji era began, many Westerners began to visit Hakone, and the town began to take on a more Western-oriented character as a resort destination. What value did Westerners of the time see in Hakone? It is said that the cool climate, even in summer, brought about by Hakone’s high altitude, had a lot to do with it. The average temperature around Lake Ashi is about 4 degrees Celsius lower than in Tokyo. They began to visit Hakone as a summer resort and health resort where they could escape Japan’s humid summers. (Incidentally, up until that point, the general public in Japan had never thought of spending the summer at a “summer resort.”) In addition to these climatic factors, there are likely also geographical ones. Hakone was relatively close to the foreign settlement in Yokohama, so Westerners could spend a night or two in Hakone on the weekend before returning home.

Today, transportation has improved, and Hakone has become one of Japan’s leading tourist destinations, attracting nearly 20 million visitors annually. Currently, more than 80% of Hakone-machi Town’s working population is employed in the tourism industry, including inns, hotels, restaurants, and souvenir shops. The hot springs scattered around Hakone are collectively referred to as the “Seventeen Hot Springs of Hakone” or “Twenty Hot Springs of Hakone.” This refers to the Edo period’s “Seven Hot Springs of Hakone,” plus hot springs discovered after the Meiji period. Currently, there are approximately 350 springs flowing from the source. The quality and efficacy of the hot springs vary by area within Hakone. While staying at a hotel with its own hot spring facility is one way to enjoy a hot spring in Hakone, there are also many drop-in hot spring facilities where you can simply enjoy the baths without staying overnight.

In terms of food, Hakone is naturally blessed with an abundance of mountain produce. Also, since Hakone is close to the seas of Sagami Bay and Suruga Bay, there is an abundance of seafood. As a result, there are many popular restaurants in Hakone. Tofu dishes and soba noodles have long been Hakone’s specialties, and it is said that the secret to the deliciousness of these dishes lies in Hakone’s water: Hakone’s spring water has long been known for its high quality. In addition, due to its history as a resort for Westerners, Hakone has many bakeries and Western restaurants.

Now, why are such abundant hot springs gushing forth in Hakone? It’s the result of Hakone’s active volcanic activity, which began approximately 400,000 years ago and continues to this day. Looking at a map, you can see that the mountains that make up Hakone form a circular chain. Inside this ring is a caldera. This caldera is quite large, measuring approximately 11 km east to west and 11 km north to south. The interior of the caldera is also uneven, containing the highest peak in Hakone, which is Mount Kami (1,438 m), as well as Mount Koma (1,357 m) and Mount Futago (1,091 m). Lake Ashi is actually a collection of water in a portion of the caldera, and the Haya River flows from the lake’s northern shore. In other words, what is commonly referred to as “Hakone” is the area centered around this gigantic caldera and the surrounding mountains.

The Hakone landscape we see today was formed approximately 3,000 years ago. At that time, a phreatic explosion caused a landslide of Mt. Kami, resulting in the deposition of a large amount of sediment, creating the current topography around Owakudani. At the same time, the sediment dammed the river, creating Lake Ashi. Lake Ashi today is a non-freezing lake located at an elevation of 724 meters, measuring 19 kilometers in circumference, 6 kilometers from north to south, and 44 meters deep at its deepest point. Today, Lake Ashi is home to a variety of fish, including smelt, rainbow trout, carp, crucian carp, and black bass. Black bass were once introduced from the United States and released into the lake, but their release is now prohibited by law due to their adverse effects on the ecosystem.

Several sightseeing boats ply Lake Ashi. While they’re practical means of transportation, they also offer panoramic views of the lakeside scenery that can only be seen from aboard ship. Among them, the most eye-catching is the gigantic, vibrantly colored “pirate ship.” Pirate ships connect three major lakeside spots: Togendai Port, Hakone-machi Port, and Motohakone Port. A direct trip from Togendai to Hakone-machi on a pirate ship takes about 25 minutes, but if you stop at Motohakone along the way, the total journey is about 35 minutes. A luxurious special cabin is available for an additional fee. As of January 2026, three types of pirate ships are in service.

Owakudani, one of Hakone’s most scenic spots, lies at the foot of Mount Kanmurigatake. Volcanic activity still continues here, creating a desolate landscape. Steam, carbon acid gases, and hydrogen sulfide gases spew forth as white smoke from numerous vents, and the pungent smell of sulfur wafts through the air. This area was formerly known as Jigokudani (literally, “Hell Valley”). However, in 1873, when Emperor Meiji and Empress Shoken visited Hakone, the name was changed to Owakudani (literally, “Great Boiling Valley”), as it was deemed inappropriate for a hell to be located in a place visited by the Emperor.

Owakudani’s specialty is the black eggs. They are made by boiling raw eggs in sulfuric acid springs at over 80 degrees for about an hour, then steaming them at about 100 degrees for about 15 minutes. It is said that eating one black egg will extend your life by seven years, and eating two will extend your life by 14 years. When boiled in the hot spring pond, the iron in the water adheres to the egg shell. When the egg is then steamed, it undergoes a chemical reaction with the hydrogen sulfide in the steam, turning it into pitch-black iron sulfide, which is generally thought to change the color of the shell. The black eggs are made every day by skilled, dedicated staff.

Sengokuhara

Sengokuhara (also known as Sengokubara) is an area of approximately 16 hectares located in the northern part of the Hakone volcanic caldera. Much of it is covered by grasslands and marshes, but portions are currently developed into vacation homes and golf courses. Sengokuhara’s pampas grasslands are a scenic spot representative of Hakone in autumn. The clusters of pampas grass that spread across the foot of Mount Daigatake (1,045m) have been selected as one of “Kanagawa’s 50 Most Scenic Spots.” The sight of the pampas grass swaying in the autumn breeze from late September to early November is often described as a “golden carpet.” While it’s enjoyable to walk along the grassland paths, pushing your way through the pampas grass, simply viewing the grasslands from a car is also good.

From 1880 to 1904, Sengokuhara was home to a vast ranch owned by Koubokusha (a company founded by Shibusawa Eiichi and others), where cows and horses were raised. At the time, the milk, butter, and beef sold by Koubokusha were popular with foreign visitors to Hakone. The gently sloping grasslands of Sengokuhara were once maintained as thatched fields for use as thatched roofing material, cattle feed, and fertilizer. Currently, to maintain the beautiful landscape of the pampas grasslands, yamayaki (literally, “mountain burning”) is carried out annually on a windless, sunny day between mid- and late March. Without yamayaki, weeds and shrubs would grow and the beautiful grasslands would be lost. Furthermore, the burned ash acts as fertilizer, encouraging the growth of new pampas grass.

Across the road from the pampas grass plain lies the vast Sengokuhara Marsh. Approximately 20,000 years ago, the area was the bottom of a caldera lake. Volcanic activity gradually shallowed the lake’s bottom with sediment, and the Sengokuhara Marsh was formed during this process of land formation. Covering approximately 17 hectares, the Sengokuhara Marsh is one of the few remaining marshes in Japan’s low mountainous areas, making it a valuable geographical site. A portion of the marsh (approximately 0.7 hectares) was designated a national natural monument in 1934. Hakone’s cool, humid climate throughout the year allows for the cultivation of marsh plants such as wild iris, Japanese thistle, blunt-leaved bogmoss, and the carnivorous roundleaf sundew.

In one corner of the marsh is the Hakone Botanical Garden of Wetlands, where 1,700 species of plants grow. This facility was established in 1976 to raise awareness of the Sengokuhara Marsh and to carefully protect the marsh environment. The facility includes the “vegetation restoration area” covering approximately two hectares, where local marsh plants are maintained and managed. In fact, entry into the Sengokuhara Marsh is prohibited in order to protect the plant growth environment. Therefore, the vegetation restoration area was established so that visitors can learn about the state of the Sengokuhara Marsh. Please note that this facility is closed during the winter.

Sengokuhara is home to several renowned art museums. The Pola Museum of Art, for example, exhibits a wide range of works from Japan and abroad. It boasts one of Japan’s largest collections of French Impressionist and Post-Impressionist works, including works by Monet, Renoir, and Cézanne. The forest surrounding the museum is home to 300-year-old beech trees, as well as Japanese stewartia and Japanese dogwood, and features a wooden promenade stretching approximately one kilometer long. Based on the concept of “the coexistence of Hakone’s nature and art,” the museum building, which makes extensive use of glass, has won numerous architectural awards. In particular, the basement cafe “Tune” is an open space filled with natural light, and the view of the forest from there has been described as “like a painting.” For information about exhibitions and closing days, please check the museum’s website or social media.

Hakone Tozan Railway

Some people may be hesitant to go to Hakone by car, worried about driving on the rugged mountain roads or getting caught in terrible traffic. However, in Hakone today, there are many well-developed means of transportation other than cars. Starting from Hakone-Yumoto Station, you can use trains, cable cars, ropeways and sightseeing boats to see many of Hakone’s popular destinations even without a car. First, let me briefly explain the Hakone Tozan Railway and the sights along the line.

The Hakone Tozan Railway is one of Japan’s leading mountain railways, departing from Odawara Station and running along the main tourist route of Hakone, including Hakone-Yumoto, Miyanoshita, and Gora. The difference in elevation between Hakone-Yumoto Station and its terminal station, Gora, is a whopping 445 meters. The Hakone Tozan Railway’s passenger cars slowly rumble up the mountain between Hakone-Yumoto and Gora in about 40 minutes, weaving their way through the Hakone mountains. When I go to Hakone by train, I usually get off the Shinkansen at Odawara Station and transfer to the Hakone Tozan Railway from there. However, if you’re coming from Tokyo, Odakyu Electric Railway’s limited express Romancecar directly connects Shinjuku Station and Hakone-Yumoto Station, so many people will likely transfer to this mountain railway at Hakone-Yumoto Station.

Hakone Yumoto is the gateway to Hakone, and for many, it’s the starting point for sightseeing. Looking at a map of Hakone, you’ll see a section of the mountains surrounding the Hakone Caldera cut off in the lower right, creating what appears to be an entrance to the caldera itself. This is the area around Hakone Yumoto. The Haya River, which collects all of Hakone’s water, flows out of this area and empties into Sagami Bay. During the Edo period, the Tokaido Highway also entered the Hakone section through Hakone Yumoto. Today, both National Route 1 and the Hakone Tozan Railway enter the Hakone area from here.

As mentioned above, Hakone Yumoto is the oldest of the “Seven Hot Springs of Hakone.” Since its discovery during the Nara period, it flourished as a hot spring resort town during the Edo period. Even today, the town retains its traditional onsen atmosphere, with large and well-established inns lining the streets. Additionally, there are plenty of day-trip hot spring facilities along the Sukumo River and Haya River, perfect for those wishing to stop by without staying overnight. The shopping street in front of Hakone-Yumoto Station is always bustling with souvenir shops, restaurants, and more. This shopping street is connected to the station by an arcade, so you don’t have to worry about rainy days.

The Odawara Horse-drawn Railway Company, founded in 1888 by seven influential figures from the Odawara and Hakone business communities, is the precursor to the current Hakone Tozan Railway. The Odawara Horse-drawn Railway ran a total length of 12.9 km between Kozu and Yumoto. At the time, its terminus, Yumoto Station, was located near the current location of Hotel Kajikaso. In 1900, the line was converted into an electric railway, and by 1919, the rails had been extended across the same steep mountainous terrain from Yumoto to Gora as they are today. The Hakone Tozan Railway currently has a sister relationship with the Rhaetian (Rhätische Bahn) Railway in Switzerland, and even operates a train named after St. Moritz Station.

As mentioned above, the Hakone Tozan Railway is a unique line, with a continuous series of extremely steep gradients, especially from Hakone-Yumoto onwards. The system used on this steep line is neither the “Abt system” nor the “cable-pulling system.” It is the most common rail-propulsion system, known as the “adhesion system.” The Hakone Tozan Railway is the steepest adhesion railway in Japan. Two- or three-car mountain trains slowly climb this line. Around Miyanoshita in particular, there are many extremely sharp curves, so much so that the front car can be seen from the rear car. Because it is a single-track line, trains going up and down pass each other at every station and signal stop.

There are three switchback points along the Hakone Tozan Railway. A switchback means that a train switches positions to climb a steep slope. For example, let’s say you board the front car of the Hakone Tozan Railway from Odawara or Hakone-Yumoto. At Deyama Signal Stop, just beyond Tonosawa, a switchback occurs, and your car becomes the last car. Then, just when you think you’re back at the front again at Ohiradai Station, your car quickly becomes the last car again at the Kami-Ohiradai Signal Stop, and you continue on to the final stop, Gora. At each switchback point, the driver and conductor, naturally, switch positions, a sight unique to mountain railways.

Another well-known attraction of the Hakone Tozan Railway is the approximately 10,000 hydrangeas that adorn the line. From mid-June to mid-July in particular, you can enjoy a picturesque train ride while admiring the hydrangeas (though the flowering period varies depending on the elevation change). Miyanoshita Station, in particular, has the largest number of hydrangeas of all the stations. The flowers come in a wide variety of colors, including blue, purple, and red. Also, in April, passengers are greeted by approximately 100 weeping cherry trees planted along the tracks near Ohiradai Station.

One of the most scenic spots along the Hakone Tozan Railway is the Hayakawa Bridge (commonly known as the Iron Bridge of Deyama), which spans the Haya River. It is the oldest surviving railway bridge in Japan and is a nationally designated tangible cultural property. The Hayakawa Bridge is located between Tonosawa Station and Ohiradai Station. As you cross the bridge, look down from the train window and you’ll be able to see all the way to the valley floor, 43 meters below, for a thrilling experience.

It takes about 40 minutes from Hakone-Yumoto Station on the Hakone Tozan Railway to reach its upper terminus, Gora. Gora is a transfer point for the Hakone Tozan Cable Car. Dotted with art museums and parks, the Gora area was a popular destination during the Meiji period as a vacation spot for business leaders and literary figures. Hakone Gora Park, an eight-minute walk from Gora Station, is Japan’s first French-style formal park, opened in 1914, and is a designated national monument. This park is also famous for its seasonal flowers, and the grounds include the Tropical Plant Pavilion, a tea room, and workshop studios.

Miyanoshita

Miyanoshita is the third station from Hakone-Yumoto on the Hakone Tozan Railway. As mentioned above, after the Meiji Restoration that began in 1868, Hakone became popular as a resort destination for international residents in Japan, and Miyanoshita in particular was a hot spring resort that many of them visited to escape the summer heat. The street lined with shops along National Route 1 is called Sepia Street, and this is Miyanoshita’s main street. Many historic shops that welcomed many international tourists from the Meiji to Showa periods still remain here, conveying the vestiges of the past. Many shops still have signs in European characters, and it’s also fun to stroll around and visit antique shops and cafes there.

The presence of the Fujiya Hotel was likely a major factor in attracting many international residents in Japan to Miyanoshita during the Meiji period. The Fujiya Hotel was a pioneer of resort hotels in Japan, opened in 1878 by Yamaguchi Sen’nosuke, the first owner, to cater to international tourists. The hotel was furnished with Western-style beds and furniture to suit Western lifestyles and served Western cuisine. Sen’nosuke had also traveled to the United States and knew how to interact with Westerners, which led to an increase in repeat customers and made Hakone known around the world. With the opening of the Fujiya Hotel, Westerners suddenly began roaming Hakone, which had previously been little more than a post station town on the Tokaido road.

Currently, Fujiya Hotel consists of several buildings. Each building displays the architectural beauty and unique style of the era in which it was built, and many are registered tangible cultural properties. The hotel’s Honkan (or the “Main Building”) is the oldest building in the hotel, built in 1891. Reflecting the trends of the time, it is a Japanese-Western hybrid building with a tiled roof and a gabled entrance. This building houses the front desk and lobby, as well as a lounge where you can relax and enjoy cakes and other treats.

Hana Goten (or the “Flower Palace”), a building that could be said to be the symbol of Fujiya Hotel, was built in 1936 and houses facilities such as an indoor hot spring pool and a classic chapel. As its name suggests, all rooms in this building are named after flowers instead of having room numbers. Fujiya Hotel also has other buildings such as Seiyo-kan (or the “Comfy Lodge & Restful Cottage”) and the “Main Dining” building, and across the street is the hotel’s annex, Kikka-so. Kikka-so was once the site of the Imperial Villa for Emperor Meiji and Empress Shoken, and Emperor Showa is said to have visited the villa many times during his childhood. Currently, the Kikka-so building is used as a Japanese restaurant, and its Japanese garden is open to the public.

One of the Westerners most closely associated with Miyanoshita is the renowned British Japanologist Basil Hall Chamberlain. It’s said that he first visited the Fujiya Hotel around 1884 (six years after the hotel’s founding). He fell in love with the Hakone environment and the hotel, so he moved his books from his Tokyo home to Hakone and built a library on the hotel grounds, naming it the “Oh-Do Library (王堂文庫).” For reference, in Japanese, “oh (王)” means “king” and “do (堂)” means “hall,” while “basil” is Greek for “king.” Until his departure from Japan in 1911, Chamberlain frequently stayed at the Fujiya Hotel, devoting himself to his research there. His 1890 book “Things Japanese” became a guide for Westerners to understand Japan at the time. Chamberlain played a major role in the internationalization of Hakone, and the promenade that runs along the Miyanoshita Valley is still affectionately known as “Chamberlain’s Walk.”

When the Fujiya Hotel first opened, it took three to four hours by horse-drawn carriage from Yokohama, where the foreign settlement was located, to Odawara. This was long before the construction of the Hakone Tozan Railway, and automobiles had yet to appear. Furthermore, horse-drawn carriages and rickshaws could only go as far as Sanmai-bashi Bridge in Hakone-Yumoto. From there, the only way to get to Miyanoshita was by foot or by palanquin. However, Japanese palanquins were reportedly too cramped for larger Westerners, making them difficult to ride. A Hakone inn then invented a vehicle consisting of a chair attached to four poles, which was a huge hit with international travelers. This vehicle, called che-ah, was carried up the mountain by four strong men, two in front and two behind. According to Yumi Yamaguchi’s book, “Hakone Fujiya Hotel Story,” at its peak, 70 to 80 che-ah were waiting at the entrance to the Fujiya Hotel, so Chamberlain likely used one on a daily basis.

However, the first Westerner to visit Miyanoshita and bathe in its hot springs was not Chamberlain. One theory suggests it was the French aristocrat Count de Beauvoir. The Count arrived in Yokohama on April 21, 1867, during a round-the-world voyage 14 years after Commodore Perry’s fleet arrived at Uraga. He arrived in Hakone the following month. The custom of “mixed bathing” remained in Japan at the time, and many Westerners have written critical observations about it. However, the Count is said to have willingly participated and enjoyed the experience without any reservations. Japan was in the midst of a turbulent period, from the end of the Edo period to the Meiji Restoration. On November 9 of that year, Yoshinobu, the last shogun of the Tokugawa shogunate, handed power back to the Imperial Court. The waves of this turbulent era were certainly washing over Hakone.

In the 1860s, when Count de Beauvoir visited Hakone, Naraya Ryokan (Naraya Inn) was the most prestigious and elegant lodging facility in Miyanoshita. Believed to have opened in the 1700s, this inn was a frequent lodging for international visitors to Hakone from the end of the Edo period to the early Meiji period. In 1873, Emperor Meiji and Empress Shoken also spent their long summer vacations here. When the Fujiya Hotel opened in 1878, fierce competition erupted between Naraya and Fujiya for accommodations for international tourists. However, when a major fire struck Miyanoshita in December 1883, both Naraya and Fujiya were destroyed. Both subsequently rebuilt their buildings, with Naraya, in particular, constructing a new three-story Western-style building. From 1893 to 1912, Naraya and Fujiya entered into an agreement under which Naraya served as an inn exclusively for Japanese guests and Fujiya as a hotel exclusively for international guests.