Miho Pine Grove (Miho no Matsubara)

Miho no Matsubara, or the Pine Grove in Miho, is a pine-fringed beach with Mount Fuji views. It has long been known as a place of scenic beauty. And it is actually a nationally designated scenic area in Shizuoka Prefecture (in the Chubu Region). The pine grove stretches about 7 km (4.3 miles) along the Miho Peninsula and has over 30,000 pieces of Japanese black pine trees.

We Japanese have an old expression, Hakusa Seishou (白砂青松), which literally means “white sand and green pines.” It is a term describing the beauty of pine trees lined along a white sea shore. And we can see from the term how our ancestors loved and valued this kind of natural beauty from a long time ago (well, I know some people say that the sand of Miho beach is not that “white” nowadays, but I hope you will use your imagination).

Miho no Matsubara was chosen as one of the “New Three Views of Japan” in 1916 along with Onuma Quasi-National Park in Hokkaido and Yabakei Gorge in Oita Prefecture (Kyushu Region). It is also considered to be one of the “three outstanding pine groves of Japan” along with Rainbow Pine Grove in Saga Prefecture (Kyushu Region) and Kehi Pine Grove in Fukui Prefecture (Chubu Region).

However, the recent popularity of this pine grove really came about when it became a UNESCO World Heritage Site in 2013 as one of Mt. Fuji’s ‘component parts’. Since then, the number of tourists increased. And the city even moved the location of the bus parking lot to a distance of about 500 meters from the entrance of the beach. They did so because they found that the exhaust fumes from large buses were causing a harmful effect on the pine trees.

Here is a question: Why did they choose Miho no Matsubara as one of Mount Fuji’s component parts, even though these two scenic spots are 40km (27mi) apart from each other? The main reason is that ‘cultural connections’ between them were strongly considered. The grove and Mount Fuji have often been depicted together in various art forms, including ukiyo-e works by Hiroshige, paintings by some famous artists and Japanese traditional waka poems. In addition, there is a religious painting called “Fuji Mandala” created in the Middle Ages, and Miho Pine Grove is included in it as if it is a part of a religious pursuit to reach the sacred Mount Fuji.

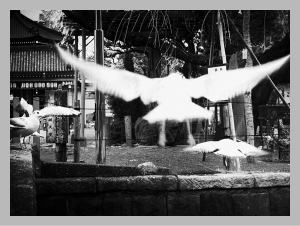

Miho no Matsubara is also known for the ‘legend of Hagoromo’. Hagoromo (feather robe) is an article of clothing worn by a celestial maiden in the folk tale. Researchers consider this folk tale has been around since at least the eighth century. Although there are some variations to it, one of the stories (the ‘Miho version’) goes like this: Once upon a time, there lived a fisherman named Hakuryo in Miho. One day, as usual, he was fishing near the pine grove. Then he noticed a beautiful robe hanging from a branch of a pine tree. It was such a beautiful and unusual robe that he thought about bringing it back to his home. He was about to take it and head for his home when a voice called out to him to stop. There is a beautiful lady standing in the shadow of a pine tree.

She said, “I am a celestial maiden, and that hagoromo belongs to me. I have just descended here to frolic because the scenery around here is so beautiful. Please give it back to me! I can’t go back to my world above without it!” She looked sad, so Hakuryo gradually felt sorry for her. He said, “OK. I will give it back to you, but in exchange, you have to dance a celestial dance for me.” And he returned it to her. Dressed in her hagoromo robe, she looked glad and began to dance gracefully. Then she started to float in the air, gradually getting higher right before his eyes, and, mixing with a spring mist, finally vanished into the air in the direction of Mt. Fuji.

The Hagoromo legend set in Miho was adapted into a Noh play in the Muromachi period (1338-1573). Since then, it has become one of the most popular and frequently performed Noh dramas. But it is not well-known that this Noh play inspired a sort of cultural exchange between Japan and France in the 1950s.

In the early 20th century, there was a dancer in France who was passionately studying the Noh play Hagoromo. Her name was Helene Giuglaris. Born in the Brittany region in 1916, she is said to have been taught the basics of dance from Isadora Duncan, a legendary American dancer, sometimes described as ‘the founder of modern dance’. Influenced by Duncan, she grew up to pursue her own style of dance and stage art, and along the way, she discovered Japanese Noh dramas.

She was especially into the Hagoromo play based on the Hagoromo legend in Miho. And she started research to perform her own Hagoromo on stage. That was in the 1940s. Due to the paucity of information about things in Japan at that time, it must have been difficult for her to do research, and it also cost her an enormous amount of money to obtain stage costumes, Noh masks, and other stage props. But at last she succeeded in performing Hagoromo for the first time in the hall of the Guimet Museum in 1949 to acclaim, and she went on to tour France with it. But it was during this tour that a terrible tragedy struck her. During a show, she suddenly fell down on stage and was carried to the hospital; and without ever returning to the stage again, she passed away in 1951 at the age of 35 from leukemia.

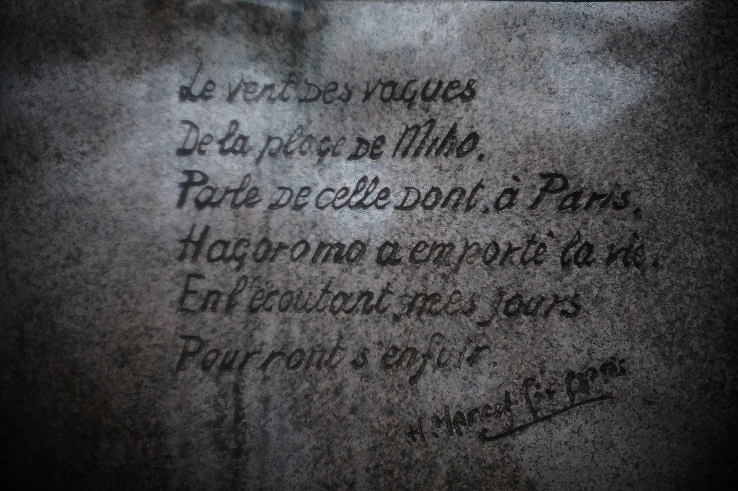

Visiting Miho, the birthplace of the Noh play, was her lifelong dream. So after her death, her husband, Marcel, her hair and stage costumes with him, visited Japan in her stead, and consoled her soul in Miho. And this story moved the hearts of local residents in Shimizu so deeply that they planned to erect a monument to commemorate her. With the help of donations from local people, the monument was completed in November 1952, and was erected near the legendary Hagoromo Pine Tree on Miho beach. The relief embedded in the monument is a work by Kyoko Asakura, a Japanese female sculptor, and it depicts Helene gazing at a Noh mask. And beneath the relief, a six-line verse written by Marcel is inscribed.

Many people, including the French ambassador to Japan and the chairman of Japan’s House of Representatives, attended the unveiling ceremony of the monument. And Umewaka Manzaburou (who subsequently became a Living National Treasure) and his theater troupe performed the Noh play Hagoromo. Years later in 1984, the first Hagoromo Festival was held in Miho, and it has been held every October since then. Festival events include the ceremony in honor of Helene, and an outdoor Noh performance of Hagoromo by the light of bonfire from evening to night.

There is no doubt that the best time to be in Miho no Matsubara is when we can see the entire figure of Mount Fuji over the pine grove under a clear blue sky. But the mountain doesn’t show us its best every day. Sometimes it is completely covered with the cloud. So, on a rainy or cloudy day, do tourists have no choice but to go back to their hotel half-disappointed after they visit the Pine Grove? I don’t think so, as Miho Pine Grove has its own charms even without the view of Mt. Fuji.

First of all, how about appreciating the beauty and strength of old pine trees? When we first step into the pine grove, we will experience a unique atmosphere, which is solemn, but at the same time refreshing. What surprises us the most is how clean the pine beach is and how well-tended the pine trees are. These are the results of the preservation efforts by local people and organizations.

Historically, people have valued the Japanese black pine because of its vigorousness, calling it ‘the king of pine tree’. It has also been considered auspicious because the evergreen color of its leaves, as well as its long life, are suggestive of our perpetual youth and longevity. So we often see it gracing the famous gardens of historical value (some may recall the 2,000 pieces of this variety planted in the Imperial Palace Garden in Tokyo). The black pine is one of the most popular trees in Japanese bonsai art. And people has used it for various purposes, such as fuel, lumber and food. In those ways, the Japanese black pine has been closely connected with people and culture of Japan. So when you stand amidst the dense pine groves in Miho, you might be able to feel something very Japanese.

Next, let me talk about Japanese traditional waka poems. Moho no Matsubara has often been used as subject matter in many waka poems, but not necessarily together with Mount Fuji. For example, the Manyoshu (万葉集), the oldest anthology of waka poems in the eighth century, contains the following waka:

Iohara no

Kiyominosaki no

mihonoura no

yutakeki mitsutsu

monoomoi mo nashi

This waka was composed by a man named Taguchi no Masuhito no Maetsukimi when he visited Kiyominosaki (present-day Okitsu Town which is relatively close to Miho Pine Grove) during his trip to Kamitsukeno no kuni (sometimes pronounced “Kouzuke no kuni,” present-day Gunma Prefecture) where he was appointed kokushi (provincial governor) in the late administrative reform in accordance with the transfer of the capital from Nara to Kyoto in 794.

The Taguchi no Masuhito no Maetsukimi’s waka roughly translates:

Viewing the abundance

Of the sea of Miho,

From Kiyominosaki

In Ihara,

There’s no worries in my mind.

It is not clear from this waka whether or not Mt. Fuji was visible on the day of his visit, but at least it is obvious that the sacred mountain did not cross his mind when he composed this poem. I guess that, even if Mt. Fuji was visible that day, it was not the majestic presence of Japan’s highest mountain but the quiet expanse of the beautiful sea that consoled his soul then, because his heart was full of “worries” due to the transfer to a far-away region.

Kitahara Hakushuu also wrote some waka poems about Miho no Matsubara, but more often than not, his focus is on the pine trees, the beach, or ships on the ocean. I like the fact that both Hakushuu and Taguchi no Masuhito no Maetsukimi composed their verses not by including Mount Fuji in the picture but by being purely impressed by the scenic beauty of the beach.

Some people think that Miho no Matsubara consists only of the pine grove and the beach. But actually the area designated as an UNESCO World Heritage site is much larger. And it includes some sections that you can enjoy in any kind of weather. Miho Shrine is one of them. Although it is not clear when this Shinto shrine emerged, people has worshipped at it from ancient times and the legendary ‘Hagoromo pine tree’ on Miho beach is the shrine’s sacred tree. A wooden boardwalk called Kami no Michi (or the ‘Road of Kami’) connects Miho Shrine with the pine grove beach. It spans 500 meters, and large pine trees of well over 200 years old surround it. These places are interesting and worth visiting for their own sakes.

Miho no Matsubara is also a place where you have a chance to eat (or buy) some of the famous local dishes or snacks from this region. There are a few shops open every day for tourists, and they sell foods such as “Shizuoka oden,” bottles of local sake, matcha ice cream, green-tea coke (aka, “Shizuoka cola”), and abekawa mochi. Chatting with shop attendants might also be fun.

Kunozan Toshogu Shrine

Next I would like to talk about Kunozan Toshogu Shrine, which is about 15-minute drive from Miho no Matsubara. (‘Toshogu’ is sometimes spelled ‘Tosho-gu’.) This is one of the most historically important shrines in Shizuoka Prefecture. The shrine is located at the top of Mt. Kuno. If you are looking for a place to go in the middle of the Japanese archipelago (between Osaka and Tokyo), this place is one of my recommendations.

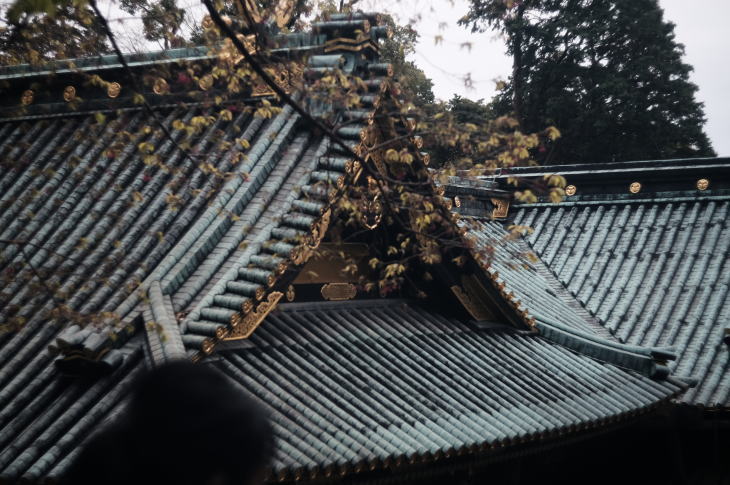

This Shinto shrine was built in 1617. And now there are thirteen structures in total in the compound. All of them are the original buildings from the early 17th century and all of them are listed as Important Cultural Properties of the nation. And the main building and its surrounding area became a National Treasure in 2010. This shrine was built to enshrine the soul of Lord Tokugawa Ieyasu and to worship him as a deity.

At the entrance of the shrine precinct stands a big two-storied gate called Romon. It was constructed around 1640 by the third Shogun, Tokugawa Iemitsu, who was the grandson of Ieyasu. There is a large tablet on the gate. The kanji characters on it were autographed by none other than the emperor of Japan at that time (Emperor Go-mizunoo). The characters can be read Tosho Daigongen (東照大権現), which roughly means ‘the Illuminator of the East’, which is the posthumous name of Lord Ieyasu as a deity.

Actually, ‘Toshogu shrine’ means ‘the shrine where Tokugawa Ieyasu is enshrined’. Among many Toshogu shrines in Japan, this one is the first Toshogu and the most important one along with Nikko Toshogu in Tochigi Prefecture. Tokugawa Ieyasu is one of the most famous historical figures in Japan. He is the first Shogun of the Edo feudal government. Edo is present-day Tokyo, and Shogun was a title the emperor of Japan gave to a feudal lord.

When Ieyasu was born in 1542, Japan was in turmoil. The nation was divided into many small countries and they always fought with each other. At first Ieyasu was just one of those feudal lords and he fought many battles himself. But finally, he won a decisive battle in 1600 (the Battle of Sekigahara), unified Japan and opened a feudal government in Edo. And this Edo government lasted for more than 260 years. It was a peaceful period (roughly speaking). So he united Japan and brought peace to the country. That is why many people still respect him.

Lord Ieyasu spent his last days in Shizuoka, until he passed away in 1616 at the age of 75. And after his passing, people immediately carried his body to Mt. Kuno according to his will. One year later, Ieyasu’s son, the second shogun of the Edo Shogunate, built the shrine there. In Shinto tradition, the soul of the person who contributed greatly to the country turns into kami (a Shinto deity), and becomes an object of worship. And when we visit the shrine and worship the person, we receive blessings of magical power by that person.

When you get to the towering Romon Gate, please pay attention to the wooden carvings above before walking through the gate. There are the carvings which depict a lion and peony flowers. The lion is considered to be the king of the animals and peony (tree peony) the king of flowers. Considering Ieyasu’s position, the lion is an appropriate symbol.

But the most interesting carvings are the ones which depict an imaginary animal called baku (pronounced as ‘bar-koo’). Baku has the nose of an elephant and the belly of a snake. And its main food is all the metals like iron and bronze. And that is why people consider it to be a symbol of peace. I mean, in the war time, all those metals are usually gathered and turned into the weapons. Then baku can’t live because of the shortage of their food. But looking at the carving there, it seems he is healthy and well-fed, which implies the world is at peace now. People think the carvings of baku represent the most important message from Lord Ieyasu: his wish for peace.

There are two statues of guardians inside the gate structure. They are protecting the shrine. If you look closely at their faces, you will find the mouth of the left one (the younger one) is wide open, and the mouth of the right one (the elderly one) is tightly closed. They say that this represents the beginning and the end of all things in this world. At the back of the gate, two sculptured guardian animals are also protecting the shrine.

After you walk through the Romon Gate, you will see a small structure called the Sacred Stable on the left. You can see a wooden carved horse inside. According to the shrine, Hidari Jingoro, a master sculptor in the early 17th century, carved the horse.

They say that, for a while after Ieyasu’s death, a real horse looking like the carving was living here. It was a horse Ieyasu loved so much. The story is told that the horse came out of the stable every night to sleep beside its master’s grave (which was in the same compound). And every morning the horse returned to the stable to eat feed. But one morning a priest noticed the horse had not returned yet. So he went to the grave to look for the horse, which was already dead there as if still sleeping. And the master sculptor, listening to the story, carved the horse and dedicated it to Kunozan Toshogu.

There is another side-story about this horse. There was a man who was in charge of looking after the horse. He was a retainer of Ieyasu. Ieyasu died on April 17, 1616, and soon afterwards he committed suicide himself in seppuku style. We call it Junshi: follow one’s master to his grave. This form of suicide was sometimes seen under the feudal system in Japan.

By the way, many structures in the shrine, including the Sacred Stable, are colored vermilion. This vermilion color comes from lacquer painting. People consider vermilion color to be auspicious. And lacquer is resistant to heat and moisture, as well as being anticorrosive and insect proof. However, it is vulnerable to the ultraviolet radiation, and extreme dryness causes cracks on the surface. That is why once in 50 years, the total recoating of lacquer for all the buildings is needed. The last one was done in 2006.

If you stand in front of the main building (sanctuary), which is a National Treasure structure in the shrine, you may think the shape of the building is a little odd. It is a sort of a complex consisting of the three different sections. Haiden, or the worship hall, is the place where people throw a coin and make their wishes. Honden, or the Main Hall, is a place where a spirit of Ieyasu resides as kami. And the small section called Ishi-no-ma (石の間), or the Stone Hall, connects these two structures.

This architectural style is very specific to a Toshogu shrine and they call it Gongen Zukuri (権現造り) structure. The floors of these halls are usually at a different level. The Stone Hall is, in a way, an anteroom to the sanctuary. Every morning a Shinto priest comes to the Stone Hall and makes an offering to kami and prays. After Lord Ieyasu died in 1616, his successor, Hidetada the second Shogun, immediately ordered the construction of the shrine. A man called Nakai, a master carpenter at that time, supervised the construction. And it took Nakai and other master craftsmen one year and seven months to complete the sanctuary building. Very fast construction for this type of structure.

The highlights of this National Treasure area include extravagant wood carvings, gold leafs and painted decorations, (needless to say the prowess of the construction work). For paintings, five different colors are used. They are natural mineral pigments and black lacquer. They are all high-quality domestic produces.

The subject matters carved or painted here were not chosen randomly but each has its own meanings. People think these artifacts reflect secret messages from Ieyasu. So if you visit the shrine, I hope you will pay attention to them and try to look for hidden messages from Ieyasu.

If you take the stone steps from the Main Hall for a few minutes, you will reach the tomb of Lord Tokugawa Ieyasu. For a couple of decades after his death, there was a small wooden shrine with a thatched roof standing there instead of the stone. In 1640, by order of the third Shogun, Iemitsu, the giant stones were brought there by ship from Izu Peninsula and processed there.

Several days before his death, realizing that his days were numbered, he uttered his final words. He said that after his death, his body should be buried in Mount Kuno, looking toward the west, the burial should be completed before the dawn, his funeral should be held in Zojoji Temple in Edo and after a year, a small shrine should be built in Nikko so that people can come to worship him. So this tomb stands looking toward the west according to his will. The reason why he said “west” is unclear, but people speculates that his birthplace, Okazaki Castle, lay in the west, and also there was a city of Kyoto in the same direction.

Let me say a few things about the death of Lord Tokugawa Ieyasu. On a day in January 1616, three months before his death, he went for hunting with his favorite falcon. Falconry was a popular amusement among feudal lords at that time.

And it was when he ate tempura of a fish called sea bream. People in Japan has believed that a sea bream is a king of fish, and they have eaten the fish mainly at festive occasions, like wedding ceremonies or New Year’s Day. Ieyasu ate the tempura of this fish and reportedly since then his health had declined. And three month later on April 17, 1616, he passed away at the age of 75. Therefore, people have long believed that the sea bream was the cause of his death. But the recent scientific studies suggest that the cause of his death might have not been the tempura but the stomach cancer. However, the truth is still a mystery.

In the center of the shrine precinct stands a bronze torii gate which was erected in the late Edo Period. It is a third incarnation. The original one was made of wood, the second, of stone. And then, after you walk through it, a short walk takes you to the steep stone steps leading up to the Karamon Gate (Chinese-style Gate). It is the formal entrance to the sanctuary area which has a tamagaki fence (玉垣).

In the Edo Period, it seems that ordinary people were not able to proceed beyond this gate. They say that only the high-ranking samurai had a right to pass under it to worship at the main building. Even today, we usually can’t pass under the Karamon Gate, except for a special occasion like a wedding ceremony or purification ceremony among others. However, fortunately nowadays, we can enter into the sanctuary area through the east entrance, bypassing the Karamon Gate and can appreciate a number of wonderful artifacts inside the fence.

The Karamon Gate structure is a collection of intricate carvings and gorgeous decorations. Although we can observe the front side of the gate only from a distance of several meters, we can see the artifacts on the back side from close up. There are various carvings here, for example, a lion’s head among some peonies, and birds perching in black pines. A high-level engraving technique called “open work” was used in these carvings. In addition, when the door of the gate is opened, the view from the back of the gate is probably one of the most photogenic of the compound, with the Pacific Ocean seen at a distance over the roof of the Romon Gate.

In China, there is a legend of a carp swimming against a strong current to reach a gate called Ryumon in order to become a dragon. This tale seems to suggest that people need to overcome various hardships to attain success. And in Japan today, we often use a term Tou-ryumon (登竜門, literally, climbing up to Ryumon) to represent ‘the gateway to success’. They say that the Karamon was designed with this legend in mind, the steep steps representing a strong current.

Getting There (English Map)

Kunozan Toshogu Shrine is about 8.5 km (5.3 miles) to the southwest of Shimizu Port and about 13 km (8 miles) to the east of JR Shizuoka Station. Since there is no train station near the shrine, using a rental car or a taxi might be the best way to get there. The shrine is at the top of Mount Kuno, and there are two ways to reach there: One is to park your car at the foot of the mountain and start climbing on foot (in this case, you need to climb up 1159 stone steps to reach the top); the other is to park your car at the top of Nihondaira hill, the adjacent mountain, and ride a cable car, which takes you to the shrine in five minute.

Other Photos

Places Nearby

Miho no Matsubara and Kunozan Toshogu Shrine are close to the port of Shimizu where international cruise ships often visit. There are several tourist attractions near the port. Among them, S-Pulse Dream Plaza is very popular. It is a four-storied commercial building that has many shops, restaurants, and amusement facilities. And, at the top of the Nihondaira hill stands the Nihondaira Yume Terrace. The view of Mt. Fuji and Shimizu Port seen from its observation deck is superb.

Conclusion

As I mentioned in this write-up, even if Mt. Fuji is not visible, there are still a few things to see and do in the Pine Grove in Miho. Also, the Kunozan Toshogu shrine is always beautiful, rain or shine. In conclusion, rain or shine either way, your tour guide will tell you some interesting things there. So, if you are thinking about visiting Japan, or if you are going to visit Shizuoka Prefecture (which is in central Japan on the Pacific coast side) on a cruise ship, please send an e-mail through the Rates/Contact page of this site.

Photographs by Koji Ikuma.

Outbound Links (New Window)