Sumpu Castle Park

Sumpu Castle (sometimes spelled “Sunpu”) was an Japanese castle built by a shogun Tokugawa Ieyasu in the central part of Suruga Province, present-day Shizuoka City (in the Chubu Region). Sumpu is an old name of Shizuoka city’s central area which lies about 150 km (about 93 miles) west of Tokyo. When the construction finished in 1607, the castle was splendid, with its magnificent donjon (main castle tower), Ieyasu’s residential palace, turrets called yagura, superb gate structures, and a triple moat system.

Sadly, these structures were all burnt down in 1635. The palace, turrets, and gate structures were restored three years later, but the donjon never was. Then, major earthquakes in the 18th and 19th centuries ended up destroying almost all the structures in the castle grounds. And they also inflicted major damage to the stone foundations. Furthermore, later in 1896, the 34th Infantry Regiment of Japanese Imperial Army filled up the innermost moat because they wanted to use this place as an army post.

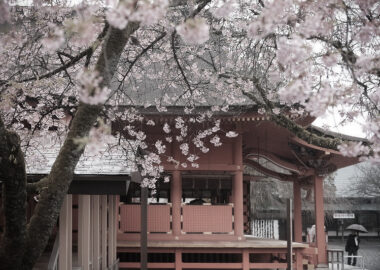

But since the end of World War Two, the castle has undergone various restoration projects. People reconstructed the East Gate and two turrets. And the excavation work began in August 2016 at the former site of the donjon. Now the former castle ground has become Sumpu Castle Park. And citizens are using the place as a recreation spot with multiple open areas for events. The park area also includes a children’s playground, a Japanese garden, and a lot of cherry trees.

Walk down the Miyuki-dori Street, one of the main arteries in the Shizuoka downtown area. Then you can see the outermost moat of the castle along the street beside you. You will also see the Shizuoka City Hall in front of you. This is an interesting structure with its unusual domed-roof watchtower section at the top. It is reminiscent of the buildings of 16th century’s Imperial Spain. Constructed in the 1930s, this City Hall structure is a national cultural asset and also a kind of symbol of the city.

Crossing the moat, you are in the section of the castle called sannomaru (third enclosure). In those days, the houses of Ieyasu’s senior vassals lined in this area. Now this section mainly has prefectural office buildings and other government-related buildings. They include the offices of the District Legal Affairs Bureau, Shizuoka Prefectural Police Department, Shizuoka Tax Office, and Shizuoka District Court. The main building of the Shizuoka Prefectural Government dates back to 1937 and is also a registered national landmark. It is basically a western-style structure made of reinforced concrete, but its roof is covered with traditional Japanese kawara tiles. Combination of Western and Japanese style was in fashion at that time.

This particular district centered around Sumpu Castle has been the political and administrative center of this region since the 14th century, well over 600 years. It was in 1586 that Tokugawa Ieyasu first entered Sumpu region officially and began constructing the ‘original Sumpu Castle’. The original castle was much smaller in area than the extended 1607 version of the same castle. Before Ieyasu, the Imagawa clan had governed this region for some 200 years. And according to studies by some researchers, it is highly likely that Imagawa’s headquarter was located within the grounds that subsequently became Sumpu Castle.

Stand by the middle moat (second moat) and gaze at the superb turrets and extensive stone walls. Then you will realize how huge the castle grounds are. When I first saw it, I was awed and wondered how much man-power was used for the construction and how much sweat and how many tears were shed.

Tokugawa Ieyasu emerged victorious from the “civil war period” in the late 16th century. After uniting the nation by conquering almost all the provinces, he got the title of shogun. And then he established a feudal government in Edo (present-day Tokyo) in 1603. But he did not stay there long. In 1605, passing the title of shogun to his son, he returned to Sumpu where he had spent eleven years of his boyhood days as Imagawa’s ‘hostage’. This ‘returning’ was actually not the ‘retirement’ because he still held his powers and continued to influence the central government in Edo.

In 1607, Ieyasu issued an order to have daimyo (provincial feudal lords) throughout Japan dispatch workers from their territories for the large-scale extension and restoration work of Sumpu Castle. This type of somewhat forceful construction order issued by the Edo-bakufu (shogunate) was called tenka-bushin (天下普請), and was often given in the Edo Period.

The number of workers each daimyo had to send was determined by the kokudaka of their land. Kokudaka (石高) was a unit based on the harvest amount of rice and other crops. And it represented how lucrative and powerful the daimyo’s territory was. So daimyo with high kokudaka had to send many workers (sometimes a few thousands of them), which was a heavy financial burden for the daimyo, because each daimyo had to bear the expenses for his worker’s transportation to and accommodation at Sumpu.

Looking at the moat of Sumpu Castle, one may sometimes wonder where all these stones came from. In fact, there were quarries at the upper parts of the Warashina River and the Nagao River. And people cut the stones roughly in these places and transported them to Sumpu. But it seems that the working conditions there were very severe. We can sense it in the old saying, Nagao Hirayama yoru wa nashi (literally, “The night doesn’t come in Nagao and Hirayama”). This phrase describes the workers’ resignation for having to work all through the night at the quarries.

One of the fun things at Sumpu Castle Park is to try to look for particular ‘markings’ chiseled by masons on some of the stones on the stone walls. Some of them are the family crests or emblems of daimyo who participated in the construction work. Obviously they would carve the markings not only for the purpose of avoiding the possibilities of mistaking one daimyo’s stones for another’s, but also for clarifying each daimyo’s assigned area of work. And I also felt that another intention was to attain a level of immortality by leaving a sign for posterity. The stones with a mark were also found at the aforementioned quarries. And that was the main reason why they could finally find out where the castle’s stones came from.

They found about 170 different markings on the stones of Sumpu Castle Ruins. And when we check each mark against the Japan’s map from the Edo Period, it turns out that Ieyasu recruited workers mainly from western Japan, a large portion of which was governed by tozama daimyo (literally “outside daimyo”). They were not long-time loyal Ieyasu’s supporters but former enemies who had just surrendered to him. Historians think that the true intention of tenkabushin lay in depriving a certain group of daimyo of their financial power in order to quell their will to revolt.

If you look at the stone walls closely, you will find a variety of stone formation and arrangements there. Some parts look old and some look very new. This stone mosaic on the wall itself tells the long history of the castle. Every time a natural disaster happened and caused damage to a certain section of the stone walls, people had to restore it. The latest restoration on a major scale was conducted from January 2010 to March 2011 to fix a wall that had collapsed in three parts. It was caused by an earthquake with a seismic intensity of “lower 6” on the Japanese scale.

The time when a particular section of a stone wall formed could be roughly traced back by checking the size of the crevices between the stones. There is a stone wall formation technique called uchikomi-hagi which became popular around 1600.

In uchikomi-hagi, the crevices between primary stones were relatively large. It was because, at that time, the stones were cut roughly and their shapes were irregular, and smaller stones were jammed in between the crevices. Then, over time, people started making the stone walls with much smaller crevices. So, if you find an uchikomi-hagi-style stone formation at Sump Castle Ruins, it might be from the Ieyasu’s reign (early 17th century).

One of the highlights of Sumpu Castle Ruins is a visit to the reconstructed East Gate and Tatsumi Yagura Turret. Local carpenters and plasterers carried out the reconstruction work. They worked hard to reproduce the authentic structures from the 17th century, with the traditional wooden frameworks and white plaster walls.

The East Gate is a majestic structure which retains the aura of the 16th century’s “warring state” period. It was the main entrance gate for Ieyasu’s senior vassels, but it also had some mechanisms for keeping the enemy off the castle grounds, such as arrow slits called yasama, holes for guns called tepposama, and murder holes (aka, rock chute or breteche) called ishiotoshi. It took five years to reconstruct this gate structure, and the work finished in 1996. Over 2000 plasterers in total are said to have been brought in.

The Tatsumi Yagura Turret (See the top photo on this page) is located at the southeast corner of ninomaru area (second enclosure) in the castle compound. Tatsumi is a combined word of tatsu (dragon) and mi (snake), meaning the southeast direction. In the medieval Japan, the names of animals in the twelve zodiac signs (in Chinese astrology) stood for directions as well as years.

Yagura (櫓), or a turret, basically had two roles; one was the role as a storehouse for keeping firearms, firewood, and food like salt or miso, in order to prepare for a siege; the other was the role as a watchtower for grasping enemy’s movement. Recently, another turret was reconstructed at the southwest corner of ninomaru. The name of the turret is Hitsuji-saru Yagura. Hitsuji (sheep) and saru (monkey) were combined to represent the southwest direction.

The interiors of all these structures are now museums. There you can learn about many aspects of the castle as well as the past and present of the Sumpu (Shizuoka) town. The intriguing exhibitions include a scale model of the main castle tower which has long gone, a miniature modal of erstwhile Sump town, Ieyasu’s armor, and several objects excavated from under the ground, including a large bronze shachihoko (an imaginary animal believed to avoid fire) that was found at the bottom of the moat.

Getting There

Sumpu Castle Park is about a 15-minute walk from JR Shizuoka Station. You can use the Shinkansen (the Bullet Train) from Tokyo (or Osaka), but not all the Shinkansen trains stop at Shizuoka. So, please be careful and check beforehand. If you come by car, it is about a 17-minute drive from the Shizuoka Interchange on the Tomei Expressway, or about a 18-minute drive from the Shin-Shizuoka Interchange on the Shin-Tomei Expressway. If you are a cruise ship passenger planning to use a taxi or a rental car from Shimizu Port, it is about a 30- to 40-minute drive (depending on the traffic).

Other Photos

Places Nearby

Shizuoka Sengen Shrine is one of the most popular tourist destinations in this area. It is about a 17-minute walk from Sumpu Castle Park. This Shinto shrine has a long history. And many structures in the shrine’s compound are the Important Cultural Assets of the nation. In particular, the magnificence of its 25-meter-tall worship hall is worth seeing. If the weather is good, I recommend you go to the Prefectural Office Observatory. There you can see a panoramic view of Shizuoka City as well as Mount Fuji in the distance.

Conclusion & Contact

If you are going to visit Japan or are looking for a private English-speaking guide around the Shimizu area (in Shizuoka), please send an e-mail via the contact form on the Rates/Contact page of this site.

Photographs by Koji Ikuma. (Featured Photo: Stone walls at Sumpu Castle Ruins.)

Outbound Links (New Window)